What Does “Integration” Mean - Part Two

A Two-Part Blog Post on Integration - Without Mentioning Switzerland Once

One of the departments I used to be responsible for at Transport for London was TfL Consulting. This arm of TfL would sell advice to other cities and countries. We used to describe TfL as “the world’s most integrated transport authority”. I think we had a reasonable case for doing so. But, in doing so, we implied that integration is a good thing, and the more integration, the better.

Well, largely that’s true - but not always.

This post builds on last week’s post that talks about integration, as experienced by customers. In that post, we described the things that need to be integrated to ensure that customers’ utility from the transport is maximised.

These things were timetables, fares, proximity between modes and ease of interchange: basically, anything that ensures customers can effortlessly flit between modes, thus ensuring they can get to as many places as possible, as quickly as possible.

This post is about the extent to which it’s useful for transport authorities themselves to integrate themselves in order to make that happen.

Types of task

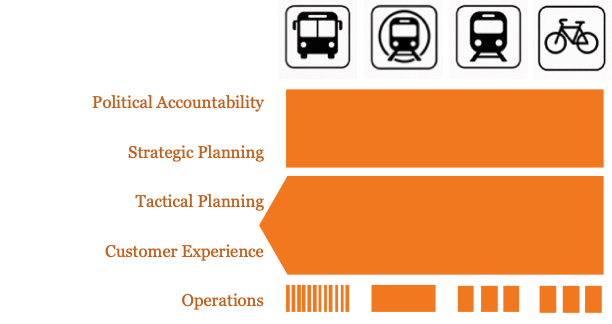

There are roughly five tasks that need to be undertaken in a typical transport system. These are:

Political accountability (given that there is normally public investment involved)

Strategic planning (big ticket investments, long-term planning)

Tactical planning (timetables, service changes)

Customer experience (fares, ticketing, information)

Operations (schedules, people management, maintenance, running the service)

It’s worth noting that pretty much everything I’ve described as necessary for integration to be experienced by the customer are in the two buckets I’ve highlighted in bold: tactical planning and customer experience. Integrate those, and the magic of integration happens.

For the purpose of this post, I’m going to describe a typical transport authority as consisting of four modes:

Train

Metro

Bus

Active travel

Obviously, some will include more and some less.

A disintegrated network

This is the current position in most counties of the United Kingdom:

In most places, there are multiple bus operators, without meaningful political accountability. The local council is responsible for all aspects of active travel provision. Network Rail is responsible for strategic planning (and some tactical planning) while a local rail operator is responsible for the remainder of tactical planning and operations.

The crucial customer experience and planning layers are delivered separately by each organisation involved, which is why you end up with a thoroughly disintegrated experience and low public transport mode shares. Different tickets, poorly coordinated timetables, bus stops not visible from train stations, no through information: all these customer experience failures that cause users to stick to their cars are caused by the institutional set-up of British counties.

Now let’s look through the opposite end of the telescope, at one of the world’s most integrated transport authorities. No, not the one I used to boast about: I mean the Metropolitan Transport Authority in New York:

That big orange block on the bottom left of the diagram is the MTA. It does its own strategic and tactical planning, defines its own customer experience and operates the trains, subways and buses in-house. You can’t get more integrated. Well, not much more.

There are, however, two major issues.

The first is that the political accountability layer is weak. The MTA is accountable not to New York City, but New York State. That’s a problem as three-fifths of the state’s voters don’t live in New York City. The MTA is unlikely to be a major issue in a state-wide election, but it’s highly likely to be a major issue for a Mayoral election. Even though the Mayor doesn’t control the MTA.

You see that currently, with the election of the Mayor of New York, where one of front-runner Zohran Mamdani’s most eye-catching policies is free bus services. However, when you drill into what he’s actually saying, he’s saying that the state (which funds MTA) should run free buses.

Well, he would, wouldn’t he…

So it’s great that MTA can do multi-modal planning, but without the right political accountability, you can’t be confident the incentives will be there for it to be done well - or the funding.

The other issue is that the streets are run by the city, not the MTA. That means that both planning and customer experience are not integrated.

So, two important lessons from New York: the accountability model has to be right, and integration needs to cover every mode.

So, let’s have a look at a city where integration does cover every mode, my hometown of London.

“Most Integrated”

This is how TfL works:

There are several important things here.

Firstly, political accountability is entirely integrated. The Mayor of London is accountable, whether or not you travel by bus, train (assuming it’s a TfL train), tube or active travel.

That’s very important, as it means voters know who’s responsible and the Mayor’s responsible for the trade-offs. Based on its most recent business plan, TfL’s currently choosing to underspend on Underground maintenance while continuing to make new active travel investments. The Mayor can make that call. I suspect that, as the tube gets less reliable, he’ll change his mind: but it’s his call to make.

Because the Mayor’s political geography and TfL’s service geography are the same, you avoid the New York problem. The Mayor’s voters are also TfL’s customers. Transport is often a major campaign issue, so the Mayor has to care.

Strategic planning, tactical planning and customer experience are all integrated across all modes. This is why London feels like it has an integrated transport service: because everything that matters is planned as one.

The operations layer, however, is highly disintegrated. In total, the actual service that Londoners use every day is delivered by around sixty different individual organisations (circa 20 bus companies, six rail companies, thirty-three London boroughs and the bike hire firm).

What’s fascinating is that this isn’t a problem. Certainly, it’s not a customer experience problem: no-one ever complains that the London Overground doesn’t feel integrated with the London Underground. Nor does it appear to be a financial problem: benchmarking is difficult, but TfL’s benchmarking report doesn’t suggest that TfL services are less efficient than other cities.

In fact, the least efficient service seems likely to be the London Underground, which is the only significant mode operated in-house.

The fact that TfL operates the tube directly (marked with a triangle in the diagram) is something of a distraction. London Underground accounts for just a third of TfL’s passenger journeys, but dominates internal conversations. Union negotiations, maintenance issues, investment trade-offs: all suck organisational airtime. In the other modes, these are the responsibility of the individual operators.

So the London experience tells us something very interesting: integration of political accountability, planning and customer experience is key: but integration of actual operations is not.

A focused transport authority

So let’s look at another city that doesn’t operate its services in-house: Stockholm:

There are a number of important differences between Stockholm and London. One is that the transport authority doesn’t run any services directly: it focuses on its crucial role of tactical planning and customer experience.

In fact, it’s interesting to see with Stockholm that the transport authority’s only area of responsibility is precisely those that are essential to delivering the integration that customers need. Look back up at the list at the top to see which are highlighted in bold. Those are the ones that need to be integrated, and in Stockholm they are.

Given that the bigger organisations get, the most bureaucratic and slothful they get, there’s a logic to making an organisation as small as possible to do the job. That’s basically what Stockholm has done. The integrated transport authority does enough to achieve customer-level integration - and no more. It’s not surprising that Stockholm appears in the top 10 (often top five) of almost every global ranking of public transport.

The second difference between Stockholm and London is that more of the strategic planning is done directly by the regional government. Whereas London City Hall has a very small transport team, with TfL doing most London-wide strategic transport planning, in Stockholm, the strategic planning is political, with only tactical planning and customer experience is done by the transport authority.

There are advantages to this.

Strategic planning should be political, so of course the politicians are going to get involved. The Mayor of London is constantly delving into TfL’s planning. By moving the official boundary in the way that has happened in Stockholm, it makes it easier for the transport delivery authority to maintain genuine independence and focus on customers.

It also means that even though the streets are owned by the city council not the transport authority, strategic planning can still be joined up.

As in London, the actual services are delivered by a myriad of different private companies, and - again - no-one seems to mind.

A Region-Wide Authority

The cities we’ve looked at so far all have different modes of integrated transport but all share one disadvantage: the integration stops at the city border. But anyone who’s stood in Euston, Grand Central or Stockholm Central will know that the wider economic catchment area for a city does not stop at the border.

Germany deals with this through the creation of transport authorities that extend beyond the core city. Here’s Hamburg:

HVV is the transport authority. Like in London and Stockholm, it doesn’t run anything itself. Like in Stockholm, it’s responsible for defining the customer experience and setting the timetables - the core activities for integration as experienced by customers.

Political accountability and much of the strategic planning are the responsibility of Hamburg City. (They also look after the roads and active travel).

However, they cannot simply decide what happens in Hamburg, as HVV (the transport authority) is owned not only by the City of Hamburg, but also the State of Schleswig-Holstein and the other regions that border Hamburg.

HVV plans and defines customer experience for the entire commuter catchment area.

This means political accountability is somewhat less direct, as HVV is owned by multiple local authorities. But it’s not the accountability gap that exists in New York, as it’s owned only by organisations that are directly affected by it.

The Ultimate Integrated Transport Authority

Now, here’s a question. If we’re trying to achieve integration, why would we not go for complete integration? Something like this:

The answer is that this organisation would be a bureaucratic monster.

If you look at the diagrams above, the two transport authorities that get closest to this are London (with the Underground) and MTA in New York. In both cases, it’s hard to see the benefit the city gets from operating the service from within the transport authority.

Indeed, this is why Paris is going through a reorganisation.

Paris’s diagram used to be nearly identical to New York’s, but with RATP as the equivalent to MTA.

Today, it is this:

If you compare that to the New York example above, you’ll see that - in many ways - it looks more disintegrated; there are certainly far more organisations involved.

But Paris has concluded - I think, rightly - that it makes sense for the transport authority to cover the full economic area, that it makes sense for there to be clearer political accountability and that the transport authority should be able to focus on timetables and fares, without the distraction of actually operating the services.

Fantasy Transport Authority

A bit like people who like football put together a non-existent fantasy team, the perfect transport authority doesn’t seem to exist.

But based on experience of some of the role model organisations above, here’s what it would probably look like:

From London it would take the breadth of modes: a truly integrated transport authority covering rail and road, with unified political accountability, planning and customer experience definition across all of them.

From Stockholm it would separate strategic and tactical planning, ensuring that the independence of the transport authority was maintained by giving the politicians formal responsibility for strategic planning, but insulating the transport authority from day-to-day meddling. It would mean that the transport authority could focus solely on tactical planning and customer experience: the things that really matter to ensuring customers experience an integrated network, and get all of the access benefits accordingly .

From Hamburg it would take the principle that the transport authority’s responsibility should not stop at the city border, but cover the whole economic region.

From most successful transport cities (almost all in Germany, Norway and Singapore), it would take the principle that the transport authority does not operate services itself, but instead contracts with professional operators to deliver on the authority’s behalf.

If we compare this fantasy transport authority with where most of the UK is right now, something immediately stands out.

Here are the two pictures side-by-side:

The ideal ‘integrated’ transport authority actually involves more organisations than the existing situation. But they’re integrated in the right way.

The current situation in the UK involves high levels of vertical integration, with each mode responsible for its own strategic and tactical planning, defining its own customer experience and delivering its own operations. Hence fragmentation and poorly joined-up services.

Whereas, the fantasy transport authority has much more horizontal integration: with a single organisation responsible for strategic planning, another for customer experience and the operations run separately. The one function which isn’t integrated at all is operations, which are run by a diverse range of organisations.

The model on the right is pretty close to the model of Singapore and Oslo, respectively, the transport authorities with the highest levels of customer satisfaction in Asia and the EU.

What does this all mean?

Well, bluntly, it means that transport authorities need to move to as close as possible to the diagram on the right.

That might mean institutional change, and it might take some time. But it can be done, as Paris has shown.

The reason why it matters is that integration is fundamental to transport delivering for transport users (here’s a reminder of the first article). It’s also wasteful to incur the costs of operating each mode but without them feeding each other.

It’s therefore important to remember that when we talk about transport integration, we’re not talking about operations. A garage manager can be as siloed as they like. What we’re talking about is the institutional infrastructure at a transport authority level: aligning contracts to deliver a common customer experience, ensuring consistent data standards for an integrated customer experience and incentives for operators that ensure they deliver joined-up journeys.

Integration is really a management layer driving a complete customer experience.

How to measure:

The success of an integrated transport authority can be measured using the access measure (as Jarrett Walker calls it), the opportunity measure (as the Welsh Government calls it) and the connectivity measure (as the Department for Transport calls it). Basically: how much useful stuff can the typical citizen reach in a defined time? The key success metric of an integrated transport authority is the most access for the smallest budget.

The operator should be managed modally with their core targets being to deliver the highest possible customer service at the lowest possible cost. It’s important that they’re only measured against cost not a full P&L, because revenue must be measured at a network-wide level. This is because fares and ticketing must be integrated, so measuring revenue modally creates endless perverse incentives.

The limits to integration

It’s also worth noting that not everything must be integrated.

Open-access rail operators, for example, thrive through not being integrated. That’s OK: they’re operating in a long-distance, competitive market. It’s a different beast to a regional transport aurhority, and should be treated as such.

Conclusion: Getting Integration Right

When people talk about “integrated transport,” they often start with transport operations. But integration as experienced by customers is driven by getting the institutional architecture right, and that depends less on who drives the buses or runs the trains, and more on who makes the decisions.

The customer experience of integration is created through shared planning, shared data and shared accountability.

Across all the examples above, a pattern emerges. Where integration works best, three conditions hold:

Political accountability matches the geography of travel - so leaders are answerable to the people who use the network. If the geography extends beyond a single political patch, then the transport authority is answerable to multiple political leaders

Tactical planning and customer experience sit together - so timetables, fares and information are designed as one coherent system. Ideally, that’s all the transport authority does, so they can be laser-focused on the crucial customer experience layer

Operations are kept arm’s length - so the transport authority isn’t distracted by Union negotiations and the price of diesel hedges.

New York shows what happens when accountability breaks away from geography. London shows the strength - and the limits - of bringing everything under one political umbrella. Stockholm shows the efficiency of a tightly focused authority, and Hamburg shows the power of going regional. Paris shows that it’s possible to change if you want to get it right.

The UK’s most recent structure does the reverse of best practice. In most counties, each mode plans and operates vertically, producing a tangle of disjointed customer experiences. To fix that, we need horizontal integration: one body defining the network as a whole, with diverse operators delivering within it. That doesn’t necessarily require bus franchising, by the way: just proper regional coordination of times and tickets.

Remember, the purpose of transport is getting people to somewhere else. As different modes suit different geographies, that means journeys need to cross between modes. When that’s too difficult, transport is less effective. The ideal transport authority achieves this - and not much else.