Big Ideas in Mini Switzerland

This article originally appeared in the September/October 2025 edition of ITS International

What would it take to grow the public transport sector in Britain by 50%?

The answer may lie where we least often look: in the thousands of towns and villages with barely a bus, let alone a train.

To understand why, we need to visit the country with the most comprehensive, best-used public transport sector in Europe: Switzerland.

In 2023, the average Swiss resident took 68 trips per year by train, up from 61 pre-Covid. The average Brit took 24, down from 28 pre-Covid. Across all transport modes, the typical Swiss travels by public transport more than 200 times every year.

The Swiss Experience

Switzerland’s rail network is twice as dense as the UK’s: about 133 km of track per 1,000 km² of territory in Switzerland, compared to 67 km per 1,000 km² in the UK. What makes it possible to sustain so much railway in a rural country? The fact that the Swiss public transport network is a miracle of useability and integration.

To explain, let me tell you about my holiday earlier this year.

I stayed in the tiny village of Paspels in the canton of Graubünden, the largest and most remote canton in Switzerland. The population density of Graubünden is 29 people per km; less than half that of Scotland and just 20% of the population density of Wales. Most of its residents live in villages.

Paspels

Paspels has a population of just 475 people. In the UK, that would be a public transport desert. And yet Paspels is served by an hourly bus to the nearest towns of Thusis and Rhäzüns.

Now, that’s good: an hourly bus to the nearest towns is excellent. But it’s what happens when those buses get to the towns that is so special.

Both arrive at a bus station immediately adjacent to the railway station. As the bus from Paspels arrives into Thusis at 59 minutes past every hour, on the adjacent platform the Regional Express train to the city of Chur also arrives. Three minutes after the people from Paspels alight from their bus, at 02 minutes past the hour, the train departs. The same thing happens at Rhäzüns.

The Regional Express train about to leave. The bus arrived immediately outside just two minutes earlier.

End-to-end Journeys

As a result, the end-to-end journey from Paspels to the capital of Graubünden can be done in less than an hour, every thirty minutes. From a village of 475 people.

That’s not all: because the Regional Express is timed to arrive into Chur seven minutes before the Intercity train to Zurich departs, Paspels is connected to Switzerland’s financial capital on the other side of Switzerland in two hours, every hour.

This is typical of how almost every village in Switzerland is connected: an hourly bus that meets a regional train that meets an Intercity train. Switzerland is like a giant animal breathing in and out on an hourly cycle of breaths. On each outbreath, buses arrive in every village in every valley across the country. On the inbreath, those buses connect to rural stations which connect to regional stations which connect to the cities.

It is this hyper-connectivity that is the key to the Swiss public transport miracle.

This miracle is what drives Switzerland’s high level of public transport usage and it’s what makes it possible for the network to sustain itself. Look back at those stats earlier: Switzerland has twice as much railway, with twice as much usage. The reason why rural lines work there but not here is that they’re fed constantly by the local networks of buses. The reasons why the buses work there but not here is that they take people to the station. This system is symbiotic.

But can we replicate that here in the UK?

Lessons from Mini Holland

From where we’re starting, it just feels an impossible task.

Nothing about the way buses and trains work in the UK is designed to the Swiss model.

Should we give up?

Well, possibly, but look at active travel. Someone looking at the UK ten years ago would have said the same about cycling. Nothing about our streetscapes was suitable for cycling. Too hard, let’s give up.

The solution emerged from Boris Johnson, of all people, when he was Mayor of London.

Let’s take a handful of relatively small places, he thought, and replicate entirely the cycling infrastructure of a Dutch city. That will prove it can be done, and become a template for others to follow. He called it Mini Holland.

I know how well this worked because I live in one of the Mini Holland locations.

Orford Road before and after Mini Holland

Do a Google Image search for the words “Mini Holland” and you will see endless photographs of the same street in Walthamstow, East London. The street is Orford Road and, as you can see, it has been analysed and re-analysed by blogs, papers, journals and academics for the last decade.

Orford Road is three minutes’ walk from my house.

From 2016, my local area was transformed into a replica Dutch city. All the main roads now have cycle lanes, all the side roads have modal filters and, most photogenically, Orford Road was pedestrianised.

It proved that these interventions are possible, and that they cause local businesses to thrive. It proved that they encourage cycling to go up and traffic to go down.

So what about Mini Switzerland?

When the pandemic happened and other towns and cities wanted to introduce what had, by then, been christened Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, there was both a playbook and an evidence bank from Mini Holland.

So, in that context, let me introduce Mini Switzerland.

In the Hope Valley, a charming slice of rural England towards the north of the Peak District, we’re taking exactly the same approach.

The Hope Valley already has one of the most important constituent features of the Swiss transport model: an hourly clockface rail service.

Let us imagine we live in Bradwell, a village in the Hope Valley located just three miles from a railway station with a population three times the size of Paspels. Today, if we wished to go to Manchester, we would almost certainly drive: despite the fact that the journey of 30 miles typically takes around 90 minutes due to the condition of the local roads.

Why would we not go by public transport? It’s not like there isn’t any. There’s a bus from, for example, Bradwell roughly eight times a day. But it’s hard to remember when: the times are 0842, 1112, 1336, 1612 (etc). If this were Switzerland, they’d be at the same minutes past the hour every day, seven days per week: lodged in everyone’s minds.

The bus goes to Bamford station, from which there’s an hourly train to Manchester. And the good news is that the bus arrives just 11 minutes before the train departs. Well, if you’re getting the 1112 that is. But the 0842 and the 1336 miss it by miles. And, anyway, 11 minutes is quite a long wait. In Switzerland, it would be a maximum of five minutes.

The tickets are priced separately and there’s no way of buying them together. Indeed it’s impossible to even get an online quote for the entire cost of the whole journey and very hard to do an online journey plan for both.

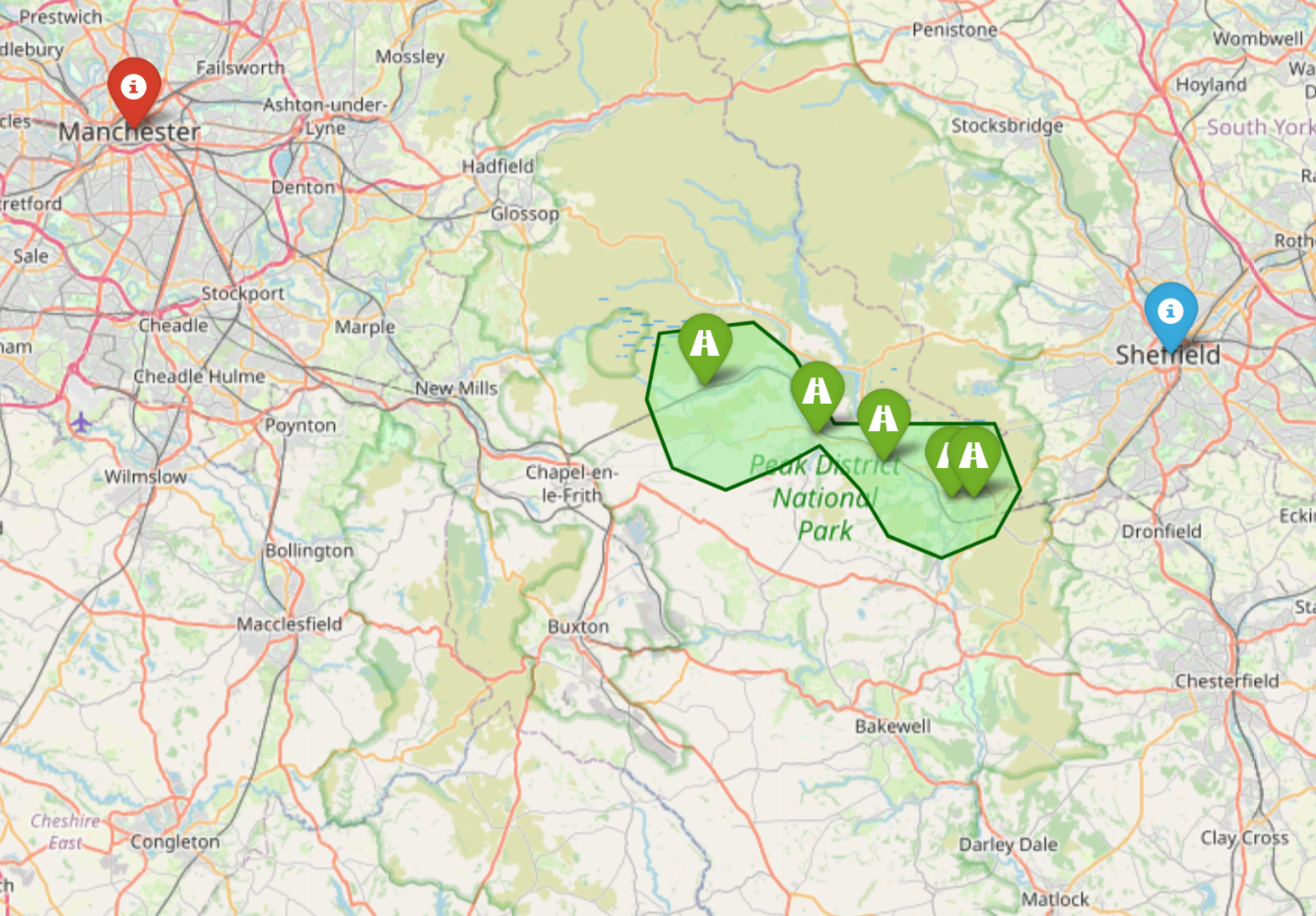

The five stations in the Hope Valley, showing their location on the Sheffield - Manchester railway.

A Place Called Hope

Do you get the point I’m making? The British state (both trains and buses in the Hope Valley are heavily subsidised) is spending a lot of money on public transport in the Hope Valley. But in the absence of the Swiss integration miracle, none of it is actually useful, other than for those with no choice.

The idea of Mini Switzerland is to do for rural transport in the Hope Valley what Mini Holland did for active travel in Walthamstow: by making a single, one-off intervention in one place, we can prove what good looks like.

This is not – yet – a Government initiative: it’s a ground-up project. In fact, it started out as a LinkedIn post. I posted the idea for Mini Switzerland, and did a call out for a local community that was ambitious enough to try it.

Hope Valley Climate Action got in touch to say they’d been having similar thoughts. Working together, we won a grant from the Foundation for Integrated Transport, and are using this to create a delivery plan.

We’re speaking to local stakeholders including the local authorities, regional authorities and operators. The great news is that there’s a real groundswell of support for Mini Switzerland: we’ve been inundated with offers of voluntary support from consultants, public transport professionals and others with expertise, all coming together to help make this a reality.

We’ve tapped into a recognition that our transport system spends too much delivering too little. Either we can accept a cycle of decline, or we can do something to show what an alternative future can be.

Where better to demonstrate that alternative future than a valley named Hope?