Cheap Flights Cost Too Much: How to Make Flying Fair

Have you ever been to a village with a ticket office?

No?

Nor had I, until earlier this year.

But, at Easter, while on holiday by Lake Como, I visited the stunningly beautiful lakeside village of Corenno Plinio.

I went early in the morning at 8AM while my teenage daughter was still asleep, so the village was deserted. But it is so swamped with visitors during the day that the villagers have clubbed together to install barriers and a ticket office.

Who can blame them?

If they’re going to live with strangers peering in at their windows, they might as well get something back.

The reason I was up so early is that I’d learned in Prague last year that this is the only way to make tourism work.

From 9AM onwards, central Prague is unbearable.

So we would get the train out to quiet Bohemian towns for lunch and I did all my tourism in Prague in the early mornings.

It’s a curious place to be first thing in the morning. The only people out are delivery drivers, street cleaners and lots of Chinese couples in full wedding dress. It’s conventional in China for the honeymoon photos to be taken in the same clothes as the wedding, so couples have to organise a wedding-style photoshoot. This is incompatible with crowds, so they were up early doing it. I’d only had to pull on my shorts and a shirt. I dread to think what time they’d had to get up given the complexity of the dresses and the perfection of the makeup.

We have now reached a ludicrous situation.

You cannot read a Sunday paper without an article about revolting locals in a tourism hotspot. Entire areas of central Barcelona and Lisbon have been gutted of residents.

In case you think this is hyperbole, I have personal experience.

The block of flats in Chalk Farm that I was born and grew up in (and in which my mum still lives) is now almost entirely Airbnb. My mum, whose flat is on the top floor, is like a survivor floating on an iceberg of holiday rentals.

It’s very clear that people who live in the places where holidaymakers wish to go aren’t very happy.

Yet, as I found in Prague and Como, holidaymaking in these places is also a miserable experience.

Who’s winning?

Too many holidaymakers

The problem is that there are too many holidaymakers.

In the last twenty years, the number of internal tourist arrivals globally has increased from 800 million to 1.3 billion, a 63% increase. The problem is that the number of places tourists wish to visit has not increased by 63%: they’re just squashing into the same old ones.

Now you could argue that this would be fine and a matter of personal choice. When it becomes too unbearable, people will start making different decisions.

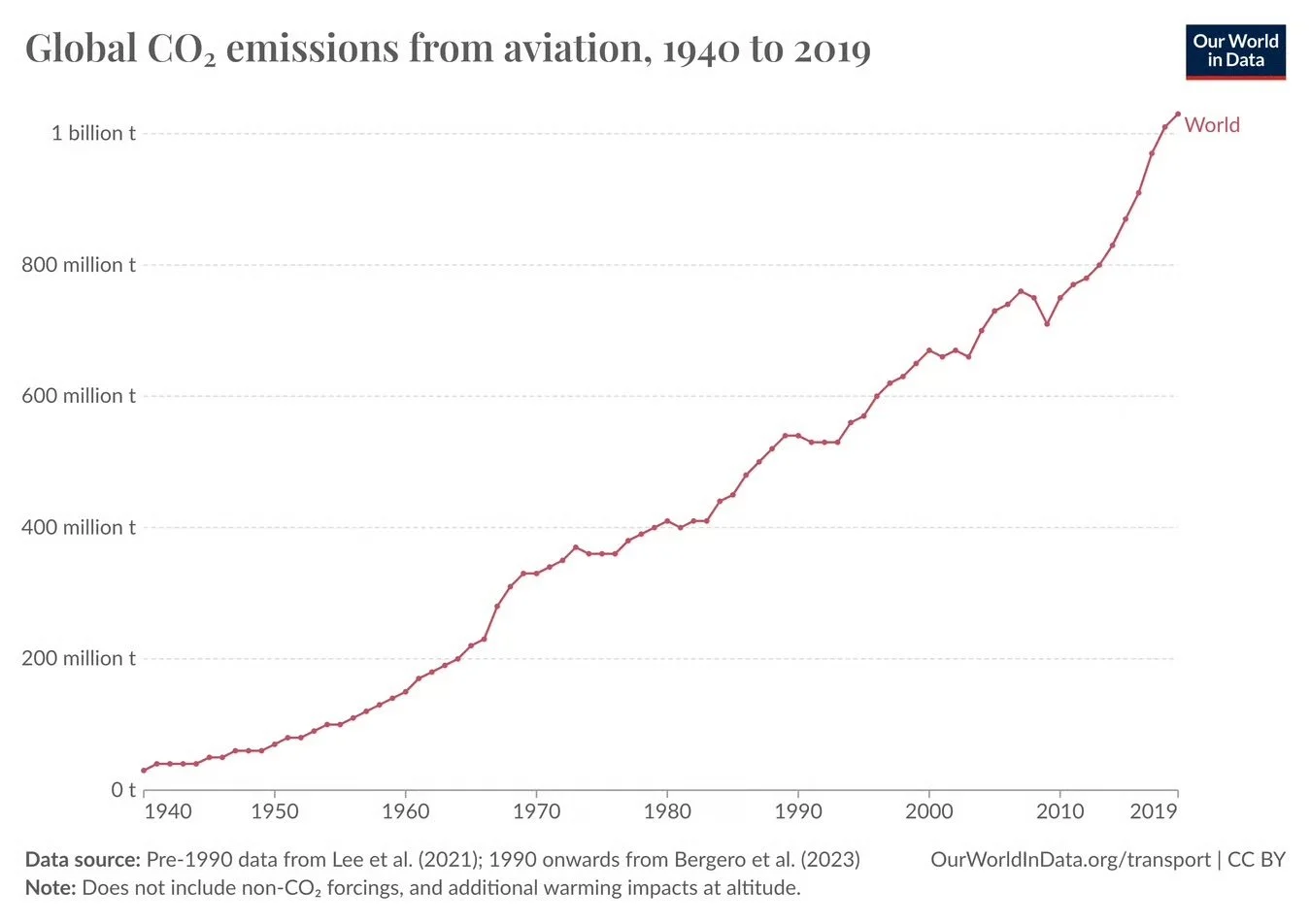

But this ignores the carbon impact. Aviation emits 1 billion tonnes of CO2 every year. When the Kyoto treaty was signed in 1997, it was around 600 million. Aviation emissions are on a rapidly rising trend. This graph cuts off before the pandemic but the pandemic marked only a blip.

Lots of people say, “this is only 2.5% of the total”, as if a single sector emitting the same as Japan: a country of 122 million people and the world’s fourth largest economy somehow doesn’t matter.

But it does matter. No country or sector is more than a few percentage points: we have to cut all of them.

The truth of where we’ve got to is that the mass flood of tourists isn’t working for locals, holidaymakers or the planet.

So we need to change something.

Frequent Flyer Levy

The good thing is that this is an unusually easy one to fix: we just need to create a frequent flyer levy.

The idea is straightforward. Everyone gets their first return flight of the year* tax‑free, or at a very low rate. After that, the tax rate rises steeply for each extra return flight - making the third, fourth and fifth trip vastly more expensive. In practice, this could look like a tax of £50 on your second return flight, £150 on your third, £400 on your fourth and so on. The steep progression would encourage people to spread their trips further apart, switch to rail where they can or simply holiday closer to home. Crucially, it doesn’t stop a typical British family from having a typical British holiday.

A frequent flyer levy is designed to be fairer than a flat tax.

Unlike a flat increase on all tickets (which would hit a family of four going on their one overseas trip just as hard as someone taking 15 flights a year), it concentrates the financial incentive on the tiny proportion of people who fly most often.

In the UK, for example, it’s estimated that just 15% of people take 70% of all flights. The Climate Change Committee has pointed to this imbalance too. Curbing emissions from this small but prolific group is where the most carbon can be saved.

This kind of tax would be difficult for many sectors but it works for aviation as security and safety means airlines already have accurate passenger lists, backed up by robust identity documents.

And the savings could be substantial. Modelling from campaign groups like Possible and the New Economics Foundation suggests that a well‑designed frequent flyer levy could reduce UK aviation emissions by around 20% to 25%, a cut of up to 8 million tonnes of CO₂ per year. Scaled up globally, the impact could arrest the upward curve of emissions.

And by making excessive flying more expensive, it would help fix the horror of central Prague.

Of course, people will still travel by air. Which is fine. But the levy's price signal would mean we finally acknowledge that a system built on ever-increasing demand for cheap flights simply isn’t sustainable.

* Maybe year isn’t the right time period. Maybe it should be two years. That will need more research. But the principle is that everyone gets a tax-free allowance.

Prague’s Old Town Square - as it never actually looks!

How will we cope?

Just fine.

There are two main constituencies who fear this idea.

The first is the hyper-mobile business traveller. Anyone who listens to The Rest is Politics will know that Rory and Alastair appear to be in a different country for every episode. This would add thousands of pounds to their travel costs each year. However, the podcast earns them “footballer money” (to quote a profile I read), so they can afford it. And if they choose to cut down a bit and group their commitments somewhat, then it’s working.

Yes, the CEOs of multinationals will continue to fly. And their firms will be willing to stump up the bill. But that’s fine; as we need the taxes. I won’t tell you which firm, but I was recently talking to the travel booker of a very well-remunerated management consultant who told me that when they didn’t like the time of their scheduled flight from London back to the US, so they demanded (and got) a private jet. It cost their firm £500k.

The second person who’ll push back will be the leisure traveller who flies multiple times a year: ski in February, Florida in August, Thailand in autumn.

Well, they’ll need to choose.

That’s exactly the point.

I really don’t want to sound all holier-than-thou, but I’m going to risk it, as I really want to make this next point: my wife and I haven’t been on a long-haul holiday for twenty years. It’s fine. There are lots of nice places in Europe.

We seldom go on holidays that require a flight in both directions. Most can be done entirely by train. We have amazing trips. Last month, I went to Vilnius by train with my daughter - a ride that involves two sleeper trains and a change of gauge. (If you are interested to know more, I’m going to be writing about 75 of them in my side-project A History of Europe in 75 Train Journeys. Sign up today!).

But I do go on planes sometimes.

In fact, I watched the Budget from a plane.

Rachel Reeves at 30,000 feet

I was travelling back from working with a client in the Middle East.

They’ve already told me they want me to go back, probably twice. I should need to tell them that I will, but it’ll cost them more as it’s my second trip. And the third will cost even more.

Might that mean that they move some of the meetings online? Maybe. If so, good! Might it mean they consolidate the visits a bit? Maybe. If so, good! Will it lose me the work? Well, maybe. And if that means that we all need to do a bit less business travel, then good! If it does none of those things, then it will raise tax revenue that can be used for climate mitigation.

Yes, there will be some families that will only be able to afford fewer trips. That’s literally the point. But no-one will be priced out entirely and it will result in happier locals, a happier planet and - here’s my guess - happier holidaymakers too.

Who wants to have to pay to enter a village?