What happened to PLCs and the stock exchange? - PART 2

A two-part post about Private equity, pension funds and the surprising return of human-to-human capitalism

The New Fat Controllers

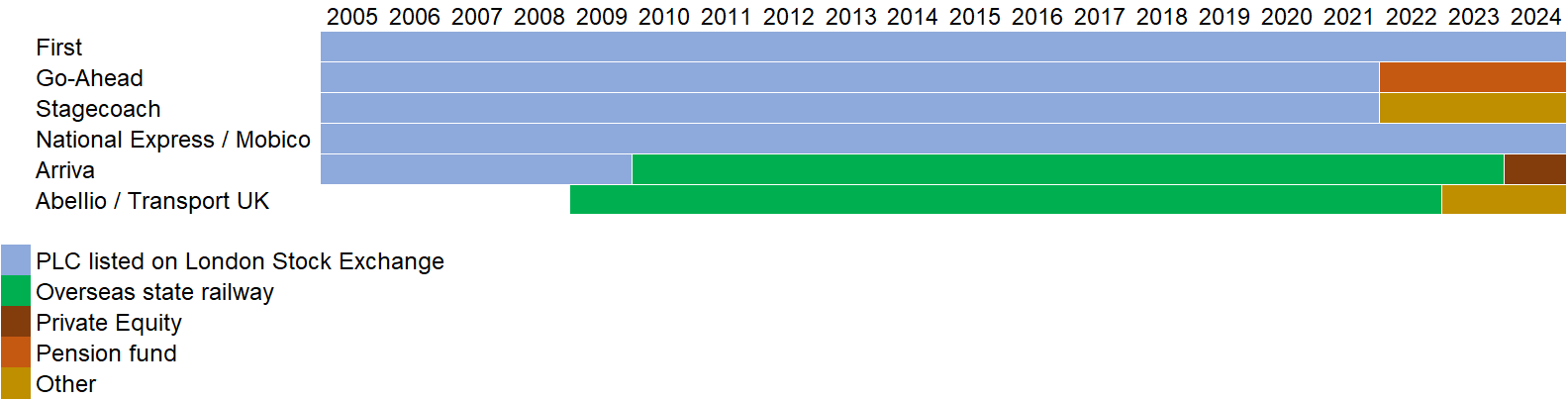

In part 1, I explored how listed companies, once the dominant players in UK transport, are slowly vanishing from the sector.

So who owns public transport today?

The answer is surprisingly varied. From private equity firms to pension funds, the new owners of Britain’s transport system bring with them new incentives, new constraints and new possibilities.

In this post, I’ll take a look at:

How Private Equity works and why it's growing

Why pension funds interested in infrastructure are buying transport businesses

What a Management Buy-Out means for a company like Transport UK

And why this shift could actually be good news for passengers and governments alike

Let’s start with the most influential of the new players: Private Equity.

Private Equity

While a PLC is owned by numerous individual shareholders, a firm like Arriva, owned by a private equity house, has single, focused ownership. Private equity houses, managed by General Partners using funds from Limited Partners (wealthy investors), aim to buy undervalued companies, improve their operations, and sell them for a profit. They aim to achieve better performance through the absence of the short-term pressures of quarterly results and from the focus (and pressure!) of the private equity owners.

Let’s look at how it works in practice.

A handful of finance folk will get together to form a Private Equity house. They are the General Partners. They go round Mayfair knocking on rich folks’ doors and seeking to persuade a significant number to put in some money. Once they’ve got enough for a fund, they close the fund. This money is now ready to be invested.

Then they scout for firms to buy.

They’re looking for firms that they believe are, in some way, undervalued. Private Equity has a reputation for asset-stripping. This is when they spot a firm where the inherent value of what they own is worth more than what the firm is getting for it. In the case of transport, it could be a bus firm with a portfolio of valuable inner-city garage sites but a loss-making bus service. It would be better to close the bus service entirely and sell the garages.

However, asset-stripping - while high profile - is not the normal Private Equity approach. Normally, they are looking for a firm with growth potential, if it’s able to invest over a longer time horizon than the normal quarterly results pulse allows.

Once they’ve identified a target, the fund buys the firm, either keeping the existing management team or appointing a new one to deliver a growth strategy. That might involve big early investments or, more controversially, asset sales. These deals typically involve borrowing, which can be contentious when it funds the acquisition rather than investment.

The management of the company now has to work (hard!) to deliver the agreed strategy, make the investments and deliver a return by the time the fund is due to return the cash to the Limited Partners. If the system is working, by the end of this period, the acquired firm is bigger and more successful (having benefited from a big investment) and the Limited Partners (the rich folk in Mayfair) get richer. The General Partner keeps a slice as well. Over the years, the General Partner becomes rich.

So rich, in fact, they can invest in Private Equity…

Of course, it doesn’t always work out like this.

But the reason private equity is becoming more and more dominant is the Private Equity-owned firms do tend to do better than PLCs.

The absence of the short-termism of quarterly results is one of the reasons. Another is that the Board of a Private Equity firm will typically comprise people who only sit on a handful of Boards and actually understand the business. By contrast, PLCs - with their thousands of investors, all owning tiny fragments of the firm - will often be a mixture of management and non-execs who sit on dozens of boards but have no real skin in the game on any of them.

A firm like Mobico (formerly National Express) benefits from the dominant role of the Cosman family, who sold their business to National Express 20 years ago but retained a slice of the enlarged company, including a seat on the Board. This is unusual.

However, none of these are the reason why one senior Private Equity manager told me recently that they believe PE generates better results. For him, there is one overwhelming factor: the Private Equity house appoints the CEO, and can fire the CEO. And because they are very close to the businesess they buy, they are able to watch closely if the CEO is delivering the agreed strategy.

One of the fascinating things about this is that in a world in which algorithms and AI have made decision-making instant (and in which it is possible to become rich programming ever faster computers to execute trades automatically), the dominant trend is for the replacement of computer-based trading with human-to-human deals and personal management supervision.

Private Equity folk spend their time raising money from Limited Partners (in person) and then buying firms (in person) and holding the CEO’s feet to the fire (in person).

It’s a 21st-century trend with 19th-century practices.

Pension funds

We have an ageing population. Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world's population over 60 years will nearly double from 12% to 22%. That’s an additional billion elderly mouths to feed. Pension funds have more money than ever, and need to make a lot more of it.

The great thing about pension funds is that they get their money now, and don’t need to spend it for decades. So they are that rarest of things: an investor who describes themselves as a long-term investor who actually is a long-term investor.

Pension funds are keen to find ways of investing cash now that will generate a fat return by the time they need to pay out the fund.

But there’s a sting in the tale. Unlike other types of investor, they absolutely must deliver a fixed return, as they have commitments to a defined number of pensioners. So we’re in the frustrating position of having a great pool of capital that can be deployed for a nice long period of time, but not if the return is risky. And here’s the thing about investment returns: they tend to be risky.

That’s why you get so many pension fund investments in infrastructure. The M6 Toll is owned by pension funds. So is the Thames Tideway tunnel. Projects that involve lots of upfront expenditure but with more or less guaranteed returns (even if they take a long time) are ideal pension fund investments.

I’ll be honest: I was surprised when Go Ahead was bought by pension funds. Public transport isn’t a giant sewer. It is a competitive market and people have alternatives. And bus operations is not all that capital intensive;' not like building infrastructure. But as public transport in this country becomes more regulated and risk migrates to the public sector, it becomes more suitable for pension funds.

Being responsible for capital investment in vehicles but not taking revenue risk feels more pension-y than the old swashbuckling Stagecoach entrepreneurialism of the 1990s.

Management Buy-Out

I’ve never seen Dominic Booth in a top hat, but becoming your own not-actually-Fat Controller is the final of the owning models that didn’t exist twenty years ago. Of course, management buy-outs aren’t remotely new (Chiltern Railways, where I worked for seven years, started out as one). But Transport UK is the first large-scale management buy-out since privatisation.

A management buy-out is when the management team of a firm raise money (often from banks) to buy the firm they lead. Typically they will do so when they believe that they can do a better job than the numpties currently in charge, though I’m sure Dominic Booth didn’t think the Dutch Government were numpties.

It is also a way of unlocking investment. Dutch state operator NedRail will have had to prioritise capital between Abellio in the UK and all its various domestic commitments. A management buy-out allows the management team to assemble its own pool of investment capital that it can both control and deploy.

In many ways, it is similar in dynamic to Private Equity. Just as the Limited Partners want their money back (plus more of it) on a specific day, so too will the bank. In the meantime, though, the management team have a lot of flexibility.

Reasons to be Cheerful

One of the things that really stands out is just how diversified the ownership structure of the big Groups has become in the last couple of years:

I’m going to choose to be optimistic about this.

Different capital structures means firms with different approaches to risk and different abilities to raise capital.

When I was a lad, the transport sector was at peak of privatisation and all the Groups were PLCs. That meant a minimal role for the Government and the largest possible role for PLCs.

But the paucity of capital available on the London Stock Exchange combined with the tyranny of quarterly returns meant that the PLCs were not going to invest significant sums. Most of them only entered the rail business because it was capital-light. But the Government had stepped right back, creating a deregulated bus sector and a rail sector heavily dependent on franchise bids to set strategic direction.

As a result, we had a period of comparative stagnation. Big investments like high-speed rail, electrification and transformational customer propositions were simply not made.

In the 2010s it got even worse. The graph above doesn’t do justice to the extent of the takeover of the sector by overseas state railways as many of them tended to be the minority party in consortia. But these organisations combined slothful decision-making with constrained capital. It was a recipe for even greater stagnation.

We’re now moving into a very different environment.

The Government looks like becoming much more interventionist under Great British Railways. There are 10 Metro Mayors ranging from the Scottish borders (North East) to the Bristol Channel (West of England). All but one of them is Labour, meaning that Government and the Metro Mayors have a strong incentive for each other to succeed (unlike the TfL era I experienced, in which Europe’s largest integrated transport authority was treated as a political football between a Red Mayor and a Blue Government).

We can expect to see strong, forceful direction from the Mayors.

What they don’t have is money. However, that’s precisely what the new ownership structures enable. Private Equity and Pension funds are going to be tight-arsed if they’re not convinced there’s an opportunity. But if the public sector can convince that they’ve created an environment of stability in which an investment can lead to a predictable return, then the money should be there. This wasn’t the case when I was a lad.

I know of what I speak

My optimism may simply be because I’m generally optimistic.

But I’ve also seen it in action.

I spent seven years at Chiltern Railways: a company that’s been through pretty every one of the different owning models since privatisation.

It started out as a Management Buy Out (Adrian Shooter) backed by Private Equity (a bit like Abellio today). In 2002 it was sold to John Laing, an investment PLC (a bit like Stagecoach today). In 2006, it returned to Private Equity under Henderson (a bit like Arriva today). In 2008 it was sold to Deutsche Bahn, a state-owned enterprise (thankfully, like no-one today). Last year it was sold back to Private Equity along with the rest of DB’s overseas Arriva division.

In total, it’s spent eleven of the years since privatisation in Private Equity hands, plus the period under John Laing, an organisation financially wired to invest in infrastructure.

“Adrian Shooter’s favourite train” - train 168001 was the first new train built after privatisation: for Chiltern Railways

This access to capital was transformational for the Chiltern Railways route. Chiltern was the first operator after privatisation to buy new trains and went on to rebuild Marylebone station, replace single track with double track, build new stations and - in partnership with Network Rail - extend its network. This was all done under contract to Government. So the public-private model can deliver private investment for public good.

This required leadership, not just money. For Chiltern Railways, the leadership came from the late Adrian Shooter, an entrepreneur in the model of the great Victorian railway founders. That’s not where leadership is going to come from in future: the locomotive heading the train these days is public sector. But it may come from Andy Burnham and his peers.

Conclusion

Different capital structures bring different approaches to risk and investment potential. The diversification of ownership in our transport sector, from PLC to private equity via pension funds, offers the prospect of a hopeful future. With strategic direction from government bodies and robust investment from the private sector, whisper it, but we might be on the cusp of a new golden age…

It just takes leadership and - above all - strategic direction from Government. Never before has that been more important.

👋 I'm 𝗧𝗵𝗼𝗺𝗮𝘀. I help organisations like yours drive 𝗶𝗻𝗻𝗼𝘃𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻, deliver 𝗰𝗵𝗮𝗻𝗴𝗲, and achieve 𝗳𝗮𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗿 results, drawing on 20 years of leadership across public and private sectors.

🚀 I offer 𝘀𝗽𝗲𝗮𝗸𝗶𝗻𝗴, 𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗼𝗿𝗶𝗻𝗴, and 𝗰𝗼𝗻𝘀𝘂𝗹𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗴 that energise teams, shape strategies and remove barriers to change. Whether you aim to accelerate innovation, drive change, or inspire your people, I’m here to help. Let’s talk!