“Advisers Advise and Ministers Decide” is Unhelpful -and Plain Wrong

A Blog Post About Getting Government Moving Faster

Employees Are the Company

Let me tell you about my first “we”.

I remember it as though it were yesterday.

I had just turned 23 and was at my desk on the 11th floor of National Express’s coach HQ in Birmingham.

I was talking to a potential supplier for a technology project I was championing. When describing our requirements, I said “We need…”.

My heart skipped a beat as I heard myself say “we”. I was speaking not just as me, but as National Express, with its tens of thousands of employees and countless shareholders.

I felt a shiver of self-doubt.

Who gave me, a kid in their early twenties, the right to speak on behalf of my bosses like that?

Then I rationalised it.

I’ve done the hard work of assembling the requirements for this project, I understand it and I’m competent to talk about it. Later on, when we tendered, I would document these requirements and get them signed off. I wouldn’t appoint a supplier alone.

But helping the market understand: yes, I was OK doing that.

Did 23-year-old me get it right?

I wasn’t far off.

The bit I got wrong was in thinking I was talking “on behalf of my bosses”. That was wrong. By law, a company acts through its people. When an employee makes an authorised decision, that decision is the company’s — just as a department’s decision is the Minister’s. When National Express employed me, I became part of it. My bosses had jobs in which they needed to make many more decisions than I did, but I had to make decisions too.

In fact, the words “on behalf” of were just wrong. I wasn’t speaking “on behalf” of my bosses or “on behalf” of the company. When I said “we”, I was speaking as the company. That frisson I felt about becoming part of something larger was absolutely correct.

But even though I’d become part of the company, and decisions I made when employed by the company legally counted as decisions of the company, that didn’t mean I could make any old decision.

If I’d phoned up National Express’s fuel hedging provider and placed a large bet on the value of crude, it would not have counted as “the company” acting. The company would only be bound by my decision if it was backed up by the authority of my role - whether written or implied.

When I had done that quick mental tabulation and concluded that, yes, I was OK to say “we” when talking about the project I was championing, I was dead right. The CFO could have done the same thing for fuel hedges and the Chief Engineer for braking standards. The CEO, by the nature of their role, could do it for almost anything (though that didn’t mean they should).

Different companies choose to label these authorities in different ways. Some have very tight schedules of delegated authorities. Others, like Chiltern Railways, were a lot lighter-touch and had a presumption that competent people had the authority (indeed, an obligation!) to make decisions to further the company’s interests.

Both are fine.

The crucial point here is that everyone in the company can make decisions as the company.

How do you decide?

It’s all very well saying that everyone can make decisions, but what should you decide?

That’s where strategy comes in.

If I drop a hundred people into different places in London and tell them all to navigate to Tower Hill, most of them will get there. People who know London well or are good with Google Maps will be more confident, but everyone will get to the same place eventually.

That’s what it’s like working in a company with a clear strategy. The strategy describes the destination (Tower Hill). It might suggest some approaches (Citymapper, Google Maps, your own knowledge of London) to help you reach the destination.

But everyone’s starting from their own place, so everyone needs to find their own way. Everyone makes their own decisions, knowing that everyone else is aiming for the same destination.

If, however, I drop a hundred people into different places in London and tell them all to navigate without telling them the destination, chaos would ensue. Many would just stay where they were. Others would flail around aimlessly. The decision to stay still or to give it a go is still a decision - they just won’t have particularly useful results in getting everyone to the same destination.

That’s what it’s like working in a company without a clear strategy.

Everyone has to make decisions in a company, but you’ll get much better decisions if there’s a strategy.

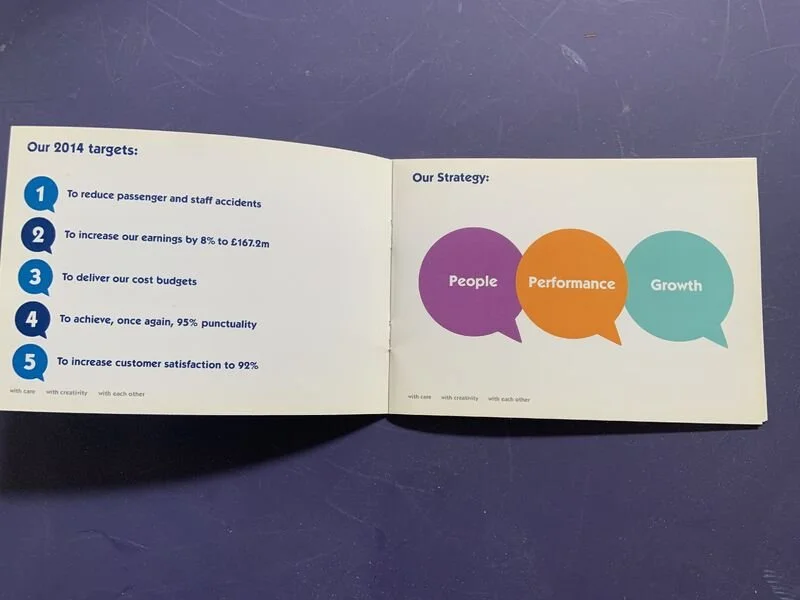

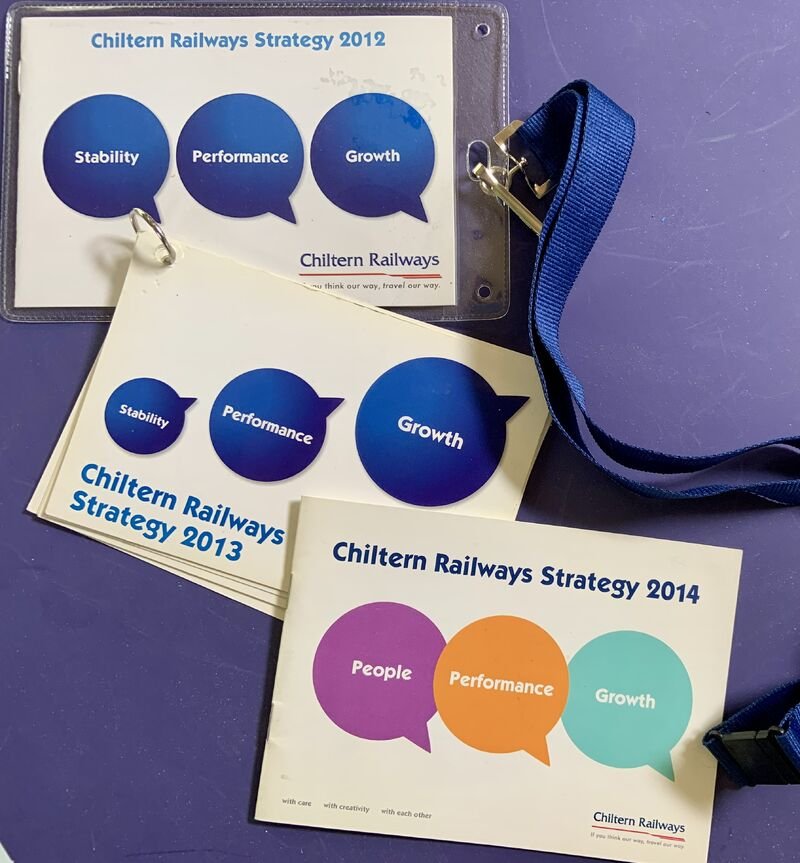

That’s why we put a lot of effort into creating a simple, clear strategy at Chiltern Railways. We made it a booklet short enough to fit onto a lanyard, we boiled it down to a memorable three-word summary, we ensured it was consistent year-on-year, and we (as directors) handed a copy to every single member of staff, explaining in person what it meant.

Having done all that, we could then allow people a lot of latitude in making decisions.

“Advisors Advise, Ministers Decide”

Anyone who’s had any contact with central Government knows that things work differently there.

You’ll be working with an official trying to get a decision and you hear the dreaded words “It’s on the Minster’s desk”.

By which they mean, I’ve made a recommendation, it’s been sent up (often via multiple layers of bosses) to the Minister, who will need to make the actual decision.

As you’ll know if you’ve been in this situation, you’ll know that “the Minister’s desk” is something of a black hole.

Recommendations sit on this desk for months. Often many months.

Ministers are, after all, very busy people.

Their core job is taking legislation through Parliament, which means hours on the floor of the House of Commons. They are also MPs, which means multiple whipped votes every week and a huge constituency case-load. They’re the PR person for the department, so constantly asked to do press photos, speeches and interviews. They’re also one of the most senior members of their political party.

It’s no wonder they rarely get back to the famous “desk” and actually read the recommendations.

It is, of course, farcical.

While there are big decisions that genuinely do need to be made by the Minister, many of the decisions on the Minister’s desk are on topics they can’t possibly understand, and so - when the moment finally comes - they will either reject out of ignorance or accept by default.

Neither is useful.

The only way to make this system remotely manageable would be to increase the number of ministers, but that would mean each was taking more and more siloed decisions. To an extent, this is the approach we’ve gone for: the number of ministers has roughly doubled from 60 in 1900 to 118 today.

In many ways, the opposite might seem healthy: wouldn’t it be a good idea for multiple policy areas to be considered together?

Well, those of my generation will remember John Prescott’s so-called SuperMinistry of the Environment, Transport and the Regions.

It made so much sense!

These three policy areas are complex and connected, and it would be far better for one organisation to be responsible for all of them.

But, of course, with one massive minister’s desk at the centre of it all, the whole thing became unviable.

I imagine if Prescott ever tried to punch his desk in frustration, the effect was muffled by mountains of paper.

As we know, his SuperMinistry was a disappointment, barely achieving anything meaningful in the time it existed. At the end of New Labour’s first four-year term, it was dissolved.

It seems like the system checkmates you either way: either ministers’ remits are so narrow the decision-making is siloed and ineffective, or so broad that ministers never make any decisions at all.

Wouldn’t it be better if, instead, the thousands of civil servants in each department could make decisions themselves, keeping things moving and freeing up the minister’s time anc concentration for the big strategic calls?

That’s how it would work in a company, after all.

A century of getting it wrong

Well, yes, that would be lovely but we all know…. it doesn’t work like that.

Government isn’t like a company: ministers are elected to make decisions, and officials are there to make recommendations and to implement those decisions.

That’s how the Civil Service works and there’s nothing you can do about it.

(If you’re talking to someone particularly eloquent, they’ll also quote the Northcote–Trevelyan Report of 1854, which led to the creation of an independent, impartial Civil Service).

Sorry, they’ll sigh, we’ve been doing it this way for nearly two hundred years - and for good reason.

Well, I’m afraid we’ve been doing it wrong.

You see, the Northcote-Trevelyan Report of 1854 was all about creating a meritocratic, impartial civil service, able to serve any Government. It was designed to ensure that Ministers would always have capable people able to make their policies happen, including immediately after an election.

It was designed to avoid the problem that we used to have in early Victorian Britain of incompetent idiots being appointed just because they knew the Earl of So-and-so. It also avoided the problem that they still have in the USA where huge swathes of the Government are replaced after each election, leading to paralysis and loss of institutional memory.

The British Civil Service was designed to ensure that, as Sir Humphrey put it, “the process of Government could go on, even when there are no ministers around.”

What the Nortcote-Trevelyan Report did not say is “Advisors advise and ministers decide.”

We got there as a result of the misunderstanding of a court case.

The Carltona Paradox

The court case in question was Carltona Ltd v Commissioner of Works 1943. It was this case that set the all-important principle that every decision made in a department is made by the Minister.

Once ministers understood that they were on the hook for every decision made in their department, they felt the need to get closer to the detail. Over the subsequent eight decades, civil servants have morphed from deciders to advisers.

The irony is that it’s a complete and utter misunderstanding of the case.

The context was that Carltona Ltd was a private food company. In 1942, the Commissioners of Works (acting through its officials) requisitioned Carltona’s factory to use for food storage and distribution to help with the war effort. The formal notice of requisition was signed by a senior civil servant, not by the Minister personally.

Carltona sued, arguing the notice was invalid as the Minister had not made the decision.

The court rejected this argument unambiguously.

Lord Greene, in passing judgment said:

It cannot be supposed that this regulation meant that, in each case, the minister in person should direct his mind to the matter. The duties imposed upon ministers and the powers given to ministers are normally exercised under the authority of the ministers by responsible officials of the department. Public business could not be carried on if that were not the case.

Constitutionally, the decision of such an official is, of course, the decision of the minister. The minister is responsible. It is he who must answer before Parliament for anything that his officials have done under his authority, and, if for an important matter he selected an official of such junior standing that he could not be expected competently to perform the work, the minister would have to answer for that in Parliament.

The whole system of departmental organisation and administration is based on the view that ministers, being responsible to Parliament, will see that important duties are committed to experienced officials. If they do not do that, Parliament is the place where complaint must be made against them.

OK, so, let’s read that back carefully.

Yes, “the minister is responsible” because the minister is accountable to Parliament.

But, “public business could not be carried on if were expected that “the minister in person should direct his mind” to every matter. As Lord Greene rightly identified, “the duties imposed upon ministers and the powers given to ministers are normally exercised… by responsible officials”.

And then the bit that’s caused such incredible confusion over the years: “Constitutionally, the decision of such an official is, of course, the decision of the minister.”

What this is saying is that no-one in their right mind would imagine that the Minister personally makes each decision.

Indeed, he (rightly!) foresaw that the system would be unviable if every decision actually had to cross the Minister’s desk personally. What he was saying is that the entire department acting collectively is one entity which, collectively, we give the personality of “the Secretary of State”.

If this starts to look familiar, that’s because it’s pretty similar to my “we” in Birmingham.

When I said “we” as an employee of National Express, I was speaking as National Express. I was making a decision as National Express. Just as everyone in a company becomes, collectively, the Company, so everyone in a department collectively becomes the Minister.

As Lord Greene put it, the Minister’s job is to make sure that the people taking the decision “could be expected competently to perform the work”.

This is, again, very similar to the situation with regard to a private company.

Have you spotted the irony?

The Carltona principle was all about saying that ministers do not have to decide everything. Indeed, that it would be a nonsense if they did.

But by establishing the constitutional principle that “the decision of such an official is the decision of the minister”, it created the idea that ministers decide.

From there, it was only a short step to “advisers advise and ministers decide.”

You could, if you wished, call it the “Carltona Paradox”: by establishing that ministers both can’t decide everything, and don’t have to, we ended up in a situation in which it was deemed that they can and must.

Escaping the Catch-22

Think back a few paragraphs: the way delegated decision-making was made possible in Chiltern Railways was that we, as a team of directors, set a clear and explicit strategy.

This takes time.

In Government, we’ve ended up in a catch-22, in which Ministers are swamped with decisions that they should not remotely be taking (and don’t have the competence to take effectively), which means they rarely have the time to do the more important work of defining a clear strategy for their department.

Once they’ve issued such a strategy, officials could then get on and make all relevant decisions.

As I’m sure you know from your own work with central Government, there are officials who are champing at the bit to actually get stuff done, and find the current norm of leaving decisions festering “on the Minister’s desk” desperately frustrating.

However, there are also some officials who, if forced to take a truth serum, would admit that they rather like the position where they’re not responsible for making any actual decisions and anything that goes wrong can be blamed on the Minister.

The best way to escape that Catch-22 is for the civil service to be banned from expressing the (much-stated) view that decision-making works differently in Government than in private companies.

It really doesn’t.

In both cases, there are people whose job it is to set strategy (directors/ministers) and others whose job it is to execute that strategy (employees/officials). In both cases, the employees can make any decision that they are competent to make. By making that decision, they are making it as the Company or as the Minister.

Part of the problem is that some Ministers sometimes think “If the decision is made in my name, I should personally make it”.

But that’s just bollocks.

Look at Whitehall at the moment.

The current system doesn’t result in better decisions because every decision is put on the Minister’s desk. It results in bad decisions being taken too slowly.

Ministers need to understand that these decisions are not taken in their name: they’re taken in the name of the Secretary of State. A role not a person.

It’s similar to the way all prosecutions are made in the name of the Crown.

Just because - officially - it is the Crown that prosecutes each criminal doesn’t mean that His Majesty The King needs to personally decide on the prosecution.

The whole Crown Prosecution Service makes decisions as the Crown, but the King is not involved.

We wouldn’t get better protections if the King decided that because these decisions are taken in his name, he’d better take them personally, and this is also true of Ministers.

Parliament muddies the water

One of the reasons why everyone thinks that Ministers have to take every decision is that sometimes they do.

“Eh?”, I hear you ask, “Isn’t that precisely what you’ve just been saying they don’t have to do?”

Well, for most decisions they don’t.

When a franchise agreement says “as the Secretary of State shall determine”, it really doesn’t mean the Secretary of State. It means any competent person in the Department for Transport. There’s no need for that decision to go near a Minister. Anyone who tells you it does is just plain wrong.

But sometimes Parliament does want the Minister to get personally involved.

They’ll indicate this by saying "the Secretary of State personally" in the relevant legislation.

There are also times when the Secretary of State has to act in a quasi-judicial function. Just as a judge can’t delegate their role in a court case, so the Secretary of State is acting personally in making these decisions.

This causes us transport people particular confusion, as lots of these involve infrastructure and planning.

When the Secretary of State “calls-in” a planning decision, they are acting in a quasi-judicial capacity. Another one very much present in our world is the Development Consent Order (DCO). The consequence of this can be seen in Benedict Springbett’s detailed account of the demise of the Stonehenge tunnel. As Benedict describes, the Secretary of State

“had been provided with a report by a panel of planning inspectors, which summarised the impact on some of the assets, but not the full, comprehensive reports.

The Secretary of State should have been adequately briefed on all the matters which he was legally required to take into account when making his decision.

Put another way, the Stonehenge Tunnel was struck down by a court because a civil servant failed to put a piece of paper on the minister’s desk.”

In this case, the Minister’s desk becomes highly relevant because this was a decision that the Minister must take personally.

However, the fact that these decisions exist - and are frequently subject to Judicial Review - shouldn’t make Ministers and officials more keen to push everything onto the Minister’s desk, just to be on the safe side.

Quite the opposite.

It should ensure that every decision is taken properly.

In the vast majority of cases, that means taking them nowhere near the Minister’s groaning desk, thus keeping space free for those the Minister must take personally.

Culture change

Central Government isn’t working.

That doesn’t feel like a controversial statement.

The two parties that, between them, have run every Government of the last century are currently polling a total of 35% of the vote. That’s not a vote of confidence in the way it works.

Every Prime Minister of recent years has expressed frustration but, unfortunately, they tend to want to try to centralise and take more control.

This is, of course, exactly the opposite of what they need to be doing.

Instead, Ministers need to step away from the detail and focus on setting really clear strategies for their departments.

Then, once they’ve articulated what they want, they need to empower officials to make decisions to deliver on their behalf.

Some officials will love the opportunity to move fast and make things.

Others will regret the loss of the comfort blanket.

But it’s only by re-learning the lesson that every single civil servant is a decision-maker will we get the Government moving again.

In next week’s post, we’ll talk about practical things we can do to get this culture change moving.