How to Get Government Moving Again

The Civil Service is stuck in a culture of pushing paper up to Ministers, allowing the paper to fester on Ministers’ Desks for months on end, and then be passed back down again to where it can be executed.

Often things have changed by the time it finally gets back to the official who needs it, so the whole process has to start again.

It’s no wonder that Government feels slow.

Last week, we discussed that a key reason for this is a catastrophic misunderstanding of the way decisions are taken in Whitehall that has resulted in the widespread notion that “Advisers advise and Ministers decide”.

I won’t repeat the argument from last week here (though you can read it if you want to), but the summary is: that’s just not true.

The Civil Service does not need to feel dramatically different to a private company, in which decisions are made by the person with the relevant knowledge and expertise, in real time.

But the “advisers advise” culture is well-established, so what can we do to change it?

Here are a dozen ideas to get you started.

1) State that it’s bollocks

This is actually hugely important.

If you do a ChatGPT query about “Advisers advise and ministers decide”, this is what you get:

As I explained last week, it’s just not true.

But it’s become so widespread in our thinking that the professional plagiarism machine that is ChatGPT regurgitates back to you the direct opposite of the reality.

Officials who want more accountability for decisions need to be very clear with both their Ministers and their bosses that the law is on their side. If I explain why, I’ll be in danger of repeating last week’s blog post, but read it yourself and then quote it whenever you’re challenged.

2) Make decisions Through Experiment

A view has emerged in Whitehall that “a decision” is a procedural event, and that a decision can only be seen to have been taken correctly if it was taken by a Minister and recorded in a formal memo.

But the law doesn’t care how a decision was taken, only that it was lawful, rational and fair.

Let us imagine, for example, that an official decided that - instead of commissioning a big piece of analysis and putting the conclusions in front of the Minister - they were going to fund a dozen experiments in the real world, and then scale up those that best achieved the Minister’s objectives. In this situation, the decision-making process would not have a single decision-making 'moment' but instead be a constant, iterative learning process.

Would a Judicial Review consider that the decision was made correctly?

Well, the official in question is competent to run these experiments and is doing so with the authority of the Minister. The process shows a rational connection between evidence and action. The biggest issue is that “fair” has come to be synonymous with “following a previously defined process”. So it would make sense for the official to publish a new version of this process before starting out.

Even better, the Department could publish that live experiments were now a decision-making method that the Department was going to use, thus enabling not just this official but every official.

3) Build a culture of delegation and accountability

Now that we all understand that Ministers don’t have to decide and that officials aren’t limited to merely advising, we can get on with the important work of getting decisions to the level where they make sense.

If there’s an official who understands the Minister’s goals and understands the subject at hand, they’re perfectly competent to decide.

Indeed, they should be deciding. Currently, officials and ministers are almost conspiring together to get bad outcomes, with officials (sometimes) reluctant to be held accountable for decisions and ministers demanding to make all the decisions.

Both need to be reversed.

For an illustration of just how much of a difference it can make, read this blog post about the building of our Chiltern Railways extension to Oxford.

While you’re unlikely to be involved in building a new railway, as you read it, you can immediately see how empowerment and accountability meant the job got done faster and cheaper - and better.

That could be your world too!

4) Lose the “Daily Mail Test”

Have you heard about the Daily Mail test?

It’s widespread in the public sector.

It basically means “don’t do anything the Daily Mail might criticise”.

There’s a problem, however.

The Daily Mail criticises literally everything.

The day after the final of Celebrity Traitors, the Daily Mail published this:

When you read the article, however, it turns out that there is literally zero evidence it was a fix, or that Alan’s tears were fake.

All they’ve done is found some people who posted on X that they thought they were.

There is litereally no way of avoiding being criticised by the Daily Mail, so it’s time to abandon the Daily Mail test.

5) Provide Innovation Budgets

Once we’ve lost (some!) of our fear of the Daily Mail, then allocate an amount of money to innovation experiments.

Be explicit on what the fund is for.

It’s there to enable local managers to try things - without requiring the level of certainty we normally expect.

We can justify this expenditure because of all the multitudinous evidence that the cheapest way to discover what good looks like is to try it.

But to do that, we need to be able to back peoples’ ideas and hunches and allow them to develop real-world evidence.

As you can hear in my interivew with Jonny Mood, Director of the National Audit Office, he couldn’t be more explicit: running experiments to try things in the real world is fine, and some of those experiments will fail. As he put it to me, “It's fine when you're swinging big to have a few misses in a controlled environment”. And he’s literally the guy in charge of deciding if money’s been well spent.

Not the Daily Mail.

6) Empower through Strategy

A number of years ago, I wrote this blog post which chuckled at teh fact that one of TfL’s strengths was that it is forced, by law, to write clear strategies.

Wouldn’t it be great, I pondered, if the central Government that had (rightly) made this a requirement for TfL practised what it preached.

Well, now’s the chance.

As I spoke about last week, empowerment only works if there’s absolute clarity as to the destination in mind.

The problem is that “strategy” (as interpreted by Whitehall) tends to be a very long, detailed document that takes months (frequently years) to assemble and is invariably out-of-date by the time it is published.

I’m talking about something very different.

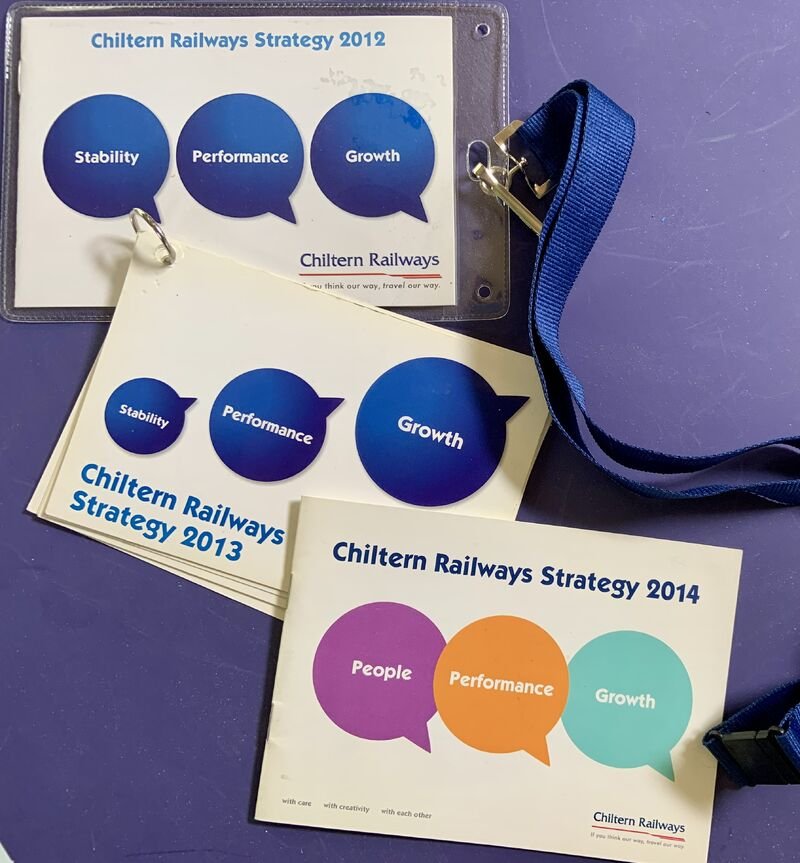

Here’s a reminder of what we meant by “Strategy” at Chiltern Railways:

Dominic Cummings rather wrecked the reputation of three-word slogans (“Hands, face, space”, “Get Brexit Done”, etc) but I’m something of a fan (of the slogans. Not of Cummings).

Ministers need to be super-clear on what they want and super-brief in saying it.

As at Chiltern Railways, make it fit on a lanyard.

7) Challenge Every Process

So often Whitehall is about Doing It The Right Way.

Challenge it when it’s not helpful.

When designing things for the public, it’s essential to consult them.

But does that have to mean a Consultation.

Consultation processes often generate far more heat than light.

Can co-creation forums be a better means of consulting? Can running A-B experiments? Can

8) Learn How to Iterate

Very few us live our lives by planning everything we’re going to do in enormous detail and then executing that written plan.

“On the 17th November 2027, I’m going to win an innovation contract with Great British Railways. That evening, I’m going to complete redecorating the dining room.”

Of course we don’t! Even if I’d very much like to support Great British Railways with their innovation (and, if their future leadership team are reading this, please note), I don’t have the agency to plan at that level of detail.

Even where I do have the agency, like redecorating the dining room, it’s ludicrous to forecast precisely when I’ll do it in two years time: what if my mum gets ill?

No, far better to say that my overall goals are that I do interesting work that matches my skills and knowledge, and that the house is kept to a decorative standard to maintain value and that my wife and I like.

At the moment, I expect that working for GBR and redecorating the dining room might be ways of achieving those goals but other, better ones may occur. In the short term, though, I’m making sure I keep up-to-speed with rail industry reform and saving enough to rededocorate a room each year.

In the same way, in our organisations, it’s crucial we know what we’re trying to achieve, but we don’t have to decide everything up front.

It’s actually far more efficient not to. I previously wrote this blog post which uses the analogy of a journey to Cornwall to try to make this point. I’m still not 100% certain if it works, so please tell me if you think it does.

If you want some confidence that this is something that Government wants to happen, then just look at the “Test, Learn and Grow” programme launched by the Cabinet Office earlier this year. They are absolutely explicit that they want projects to start with end users, build something small and iterate from there.

9) Learn what an agile and innovative organisation looks like

Organisations that are good at this stuff have norms of behaviour. Some of these are quite subtle. I described some of them in this series of blog posts.

This is where I can do a plug for my day job: I’ve spent a long time working on what makes an organisation agile.

Because you need a cheesy acronym, I’ve called it the RACE² model, but other cheesy acronyms are available.

But if you want it to add up to RACE (twice), then the list looks like this:

Resources

Authority

Culture

Expectations

Recognition

Agility

Customer Connectedness

Empowerment

Within each of those, there are norms of behaviour that collectively makes a place move at pace.

I can help you learn what they are - and identify how close you currently are to perfection with each.

10) Don’t Rely on Consultants

The British public sector sometimes struggles to delegate accountability to empowered and competent officials because they don’t exist.

The knowledge and skill that would make for a competent official have been repeatedly outsourced to consultants, with the result that the official who’s commissioning the work struggles to validate it.

As the consultant doesn’t have the authority, the result is that the decision is made by default as opposed to proactively.

Here’s my cut out ‘n’ keep guide for when to use consultants (and when not to)

11) Avoid decision-making by committee

There are certain decisions that need to be made by defined groups: frequently Boards.

They are comparatively rare.

Otherwise, there is no requirement in law that committees need to make decisions.

Committees slow things down (simply down to scheduling) and will generally moderate a decision down to a lowest common denominator of groupthink (whatever everyone’s least uncomfortable with).

So be cautious about delegating to a committee, as opposed to a person.

11) Create a Quanto

Don’t we all love a Quango?

No? Oh.

Quangos have a terribly unfair reputation.

The term stands for QUasi-Autonomous Non-Governmental Organisation.

For some reason, if 500 people work as central Government civil servants, they’re lost in the roundings.

But if their work is hived off into a dedicated body to do the same work, suddenly they’re a waste of money.

However, Quangos have a useful role, in enabling public sector organisations to renew their culture.

Transport for London isn’t a true Quango as it’s not owned by a Government department, but the moment it replaced London Regional Transport in 2000 was a moment of huge cultural renewal for transport in London.

Even though it was the same people doing the same job with the same roundel, TfL was born with a more entrepreneurial, agile, innovative culture. That was set by its first Chair, Ken Livingstone, and reinforced through the people he appointed.

The creation of Great British Railways is another such moment. It’s absolutely critical that GBR is born with the agile and innovative culture it is going to need. Its creation is a once-in-an-organisational lifetime’s chance to create it.

12) Don’t be too collaborative

We’ve ended up in a world in which collaboration is seen rather like green vegetables: the more the better.

In reality, it’s like coffee: a certain amount enhances performance but too much is actively harmful.

The public sector is a collaborative environment. But that means that multiple internal stakeholders have vetoes by default.

At the start of any piece of work, define those people who need to be involved and be explicit that this is it. Try to limit the number of those people to single digits.

It’s a culture change but, hey, all of this is a culture change.

The culture needs to change, so why not here - and with you?