“As Low as Reasonably Practicable.” Have we forgotten the “Reasonably?”

“Oh, be reasonable!” is something we’ve all said to our spouse, boyfriend or girlfriend.

But what is being “reasonable”?

That’s a surprisingly difficult question to answer.

The concept of “reasonable” comes up throughout English law. Criminal convictions must be beyond “reasonable” doubt, contracts often require consent not to be “unreasonably” withheld and negligence is when actions fall short of what is “reasonable”.

But nowhere in law is “reasonable” defined.

That inherent flexibility is the concept’s greatest strength: it is subjective and forces you to think. What would the reasonable person think? And, yes, the “reasonable person” exists in law and, no, they are not further defined.

ALARP

In the world of transport and mobility, we encounter reasonableness in the context of “ALARP”.

ALARP is a key principle in risk management, particularly in occupational health and safety. It requires that safety measures and policies must reduce risks to a level that is As Low As “Reasonably Practicable”. This involves a balance between the level of risk and the time, trouble, cost, and physical difficulty of taking measures to avoid or reduce the risk.

The law, however, doesn’t provide guidance as to what actually is “reasonable”.

Seal the windows?

One of the more memorable Exec meetings I was involved in when I was Commercial Director of Chiltern Railways involved an ALARP conversation.

This was when we still operated a handful of older mark 3 carriages with droplight opening windows in the vestibules.

The conversation we were having followed on from an extraordinary episode in which a customer had found himself on a train running non-stop to Bicester when he intended to travel to Beaconsfield.

Instead of doing what you or I would have done (travelled to Bicester and got another train back), he did what seemed to him - in that moment - the obvious thing to do. He went to the vestibule, dropped the window, waited until the train passed through a station (at 80mph) and threw himself out.

The idea, I think, was that he would then wait for a train to Beaconsfield.

He, of course, did not succeed in doing so, as he suffered multiple injuries from the fall though - thankfully and miraculously - he survived.

When the Police interviewed him in hospital, they were expecting to find evidence of mental illness, but he was quite sane. He was someone who found themselves on the wrong train and didn’t deal with it particularly well.

The conversation in this Exec meeting was what we should do.

After all, this customer had demonstrated a risk that we had not successfully mitigated: that someone could quite deliberately open the window and hurl themselves out of a moving train.

The first option was signage. After all, there was nothing in the train that advised passengers on the inadvisability of jumping out of it when it was moving. Signs are cheap and easy to put up - and is often the first response (which is why so many stations are now a festival of warnings and instructions). But would it have actually mitigated the risk? After all, there was already a notice warning not to “lean” out and, surely, he couldn’t have got to leaping without first leaning.

At the other extreme, we could have withdrawn the trains from service. This would have entirely mitigated the risk. However, it would have resulted in a significant reduction in peak time capacity. Other trains would have been overcrowded and, very likely, some people who would now have to stand every day would have decided they’d rather drive their own car. These people would then have had a vastly higher risk of death or injury than they did previously: even if the death or injury would have occurred on someone else’s network, not ours.

In the end, we concluded that the combination of door locks and signage on the trains already had reduced the risk of people falling out to the lowest level that was reasonably practicable. Preventing someone from deliberately hurling themselves out of the train could only be mitigated at disproportionate impact. Other actions, like signage, would have been performative and ineffective.

So we did nothing and it never happened again. Those carriages have now been withdrawn.

Safety first

Now, I don’t want to give you the impression that “reasonable” means easy. It does not mean that there’s no need to take actions just because they are hard to do.

We only had one Exec meeting on droplight windows but we had many on ATP.

ATP stands for Automatic Train Protection, and it was a system that prevented trains passing red signals. Given that red signals prevent collisions, this is a very good thing to do. So back in the 1990s, British Rail created two experimental ATP systems. One of these was installed on part of the Chiltern Railways route.

By 2011, the system was virtually obsolete and the manufacturer warned us of their intention to stop supporting it.

Given that virtually every other railway in the country operated without it (and was fine), surely we should just accept that and move on?

But the problem is that it was practicable to keep it going. It was a bloody nightmare and it was expensive but it was practicable. And given the nature of the risks that ATP mitigated, it was reasonable to do so.

But, of course, it wouldn’t be practicable forever.

What we were seeking to do was to minimise risk. That didn’t have to be achieved through this precise system.

So my colleagues in engineering spent many (many!) hours figuring out alternatives that would achieve the same net risk reduction across the route but with supported technology and eventually settled on an enhanced version of the industry-standard Train Protection Warning System (TPWS).

I am no longer at Chiltern Railways but I suspect that ATP (now into its fourth decade of life) is probably - somehow - still going, while the enhanced TPWS is being installed. Though maybe it’s now enjoying a well-earned retirement.

Either way, in this case, reasonably practicable meant a huge amount of hard work.

As Low as Reasonably Practicable

The problem with a flexible definition is everyone can decide what is reasonable.

If there is expected bad weather, is it practicable to reduce risk?

Yes.

Is it practicable to reduce risk to zero?

Yes.

How?

Don’t run any trains.

A number of years ago, that would have been considered an absurd solution. Yes, it eliminates risk but people who still need to travel will still travel - just on less safe forms of transport.

Here’s one of many examples: Storm Isha in January 2024.

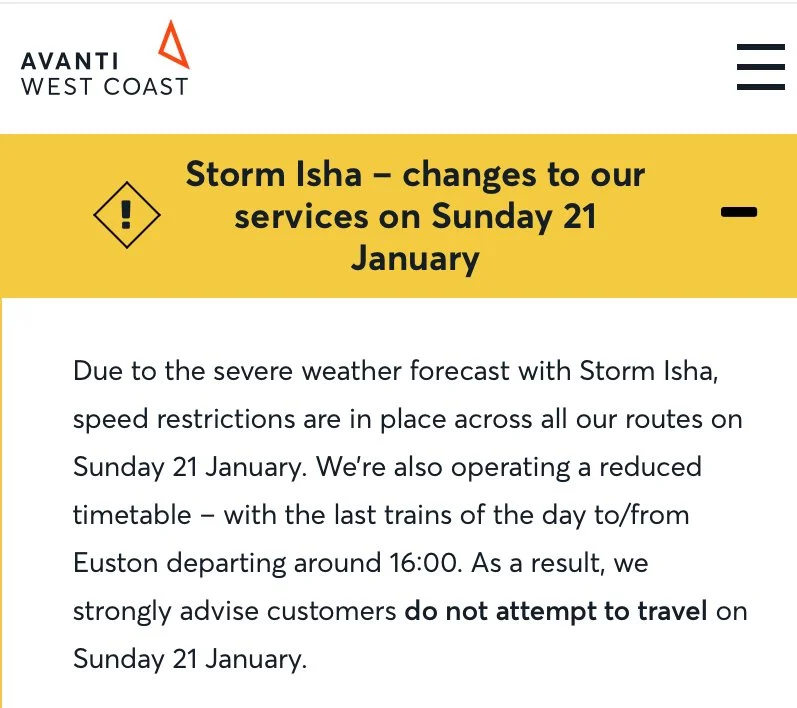

And here’s the service update for Avanti West Coast, Britain’s most important transport artery, stretching the word “changes” in the title to breaking point:

And here’s the equivalent from National Express coaches, a form of transport without dedicated infrastructure and much greater risk of collision, for the same day:

National Express could also have prevented risk by pre-emptively cancelling everything.

But while such a course of action would have been practicable, it wouldn’t have been reasonable.

As transport services are here to provide transport.

Avanti running at 125 would create unacceptable risk. But did that mean it needed to shut down entirely? What is reasonable? The folk at Avanti had to make a judgement call but the benchmark for pushing people from the safest mode of land transport to less safe modes should be very high.

Two ends of the telescope

As someone who’s spent a lifetime promoting transport innovation, I’ve certainly seen (many!) occasions when the industry’s safety culture has made innovation slower or harder to achieve.

Good!

Because I’ve also seen this question through the other end of the telescope.

Back in 2008, my then employer National Express was involved in a horrific accident. A coach overturned on a slipway of the M1. I was the nearest person to the site and was first to the hospital where the injured had been taken.

I vividly remember being the only person in the hospital with a National Express name badge. Even more vividly, I remember being in the intensive care ward in which one of our customers was lying covered in tubes and her boyfriend was shouting at me that I’d killed her.

(I do realise, obviously, that he was shouting at my name badge, not at me - but it’s a tough gig trying to apologise to someone when they are holding you responsible for a potentially fatal injury to the love of their life. I’m glad to report that she did, in the event, survive).

This is the kind of thing that can happen when a risk is not ALARP.

But the magic of ALARP is that it does include that ambiguous, ethereal, enigmatic little word “reasonable”.

It would have been utterly unreasonable to strip out ATP from Chiltern Railways just because virtually no other passengers benefited from equivalent levels of protection.

But, equally, it would have been utterly unreasonable to withdraw our slam door trains from service.

And - just as important - putting a sticker on the window would have been performative nonsense.

I’m very glad we didn’t do that.

And I’m also glad that my former Chiltern Railways colleagues kept running during Storm Isha, even when Avanti stopped.

What do you think? Is there a balance between innovation and safety? Should we have put a sticker on the window? Tell me what you think.