Complexity isn’t the issue with train fares

There is a consensus that rail fares are too complex.

There is a lot of truth to this but it’s nuanced.

It’s very important we understand this nuance otherwise we’re in danger of fixing the wrong things.

The problem isn’t exactly complexity, the problems are cognitive effort, jeopardy and arbitrariness.

Let me explain by means of a visit to Boots.

Boots

I recently bought vitamins in Boots. The packet that I wanted cost £15.99. I took two boxes off the shelves.

When I went to pay, the helpful chappie at the self-serve till told me that they were on 3 for 2. So I got another. That took the unit price (what we might call the “fare”) from £15.99 to £10.66.

However, I have an Advantage Card, so that’s another 10% off. Which means the price became £9.60.

At this point, the helpful chappie gave me a “£5 off if you spend £20 voucher” and instructed me to scan it. However, as my total order was currently £19.20, I went to buy two packets of paracetamol at 60p each, to get my order up to £20.40. With £5 off, that made the price £15.40. The price per box of vitamins was therefore £6.80.

As you can see, depending on which combination of offers I’d used, I could have paid £6.80, £9.60, £10.66 or £15.99.

But I left the shop with a very positive impression of Boots. Why?

Firstly, because it was clear to me all along why the prices were changing. 3 for 2 is intuitive. So is 10% off. So is £5 off if you spend £20. Even though I could have paid more than double what I actually paid, the prices didn’t feel arbitrary.

Secondly, I was told what to do. I didn’t have any cognitive effort to try to figure out the best price.

Even more important, I never felt any jeopardy - I did what I was told, and paid what I paid and I left without thinking any further about it. At no point did I fear penalty or prosecution.

Let me explain how it would have felt if Boots was a railway station.

At the START of the process, I’d have been faced with a touchscreen showing a range of different prices from £6.80 to £15.99. Each would have had conditions (e.g. “with Advantage Card”, “with two other of the same or similar products”, “volume rate”, etc).

I would have had to work out which of these applied to me. ‘What does “similar products” mean?’, ‘Can I use the volume rate with the Advantage Card?’. I would have feared that the machine would have sold me a ticket for a rate that wasn’t actually valid with the goods I intended to buy.

Once I had my ticket, I would have taken the vitamins I had bought off the shelf. If I’d been super smart, I’d have figured out that the best rate involved adding two paracetamol to my order but it would have seemed utterly mad - and I’d constantly be worrying that I was wrong.

All round the shop there’d be signs warning me that if I took the wrong goods for my ticket, I faced prosecution.

Once I’d taken the goods, I’d have left the shop - but there’d be inspectors outside checking that I’d got the right goods for my ticket. If not, they’d give me a penalty charge (best case) or prosecute me (worst case).

Hopefully, I’d have got it right, paid the £6.80 rate for three vitamins and two boxes of paracetamol (bonkers!! How complex!) and heaved a huge sigh of relief when the inspectors let me go.

But you can see that what a stressful experience it would have been.

You can also imagine the conversation that night in the pub “I went to boots today. Their prices are insanely complex. Turns out the best price means you have to buy two paracetamol. It’s just crazy! Someone needs to simplify their pricing structure.”

Now we get to the absolute crucial crux of this whole thing: the fare structure is identical in both experiences. The complexity is not the issue: it’s how it’s retailed.

In the first example, I had a really positive experience of Boots, with a helpful man offering me discounts. I felt good.

In the second example, I had a super-stressful experience.

As you can see, the positivity of the first experience is nothing to do with complexity and everything to do with Boots not making me figure it out for myself (cognitive effort), offering discounts that made intuitive sense (weren’t arbitrary) and not making me fear prosecution (jeopardy).

To demonstrate that these really are the problem, let’s look at two rail-based examples.

The first is my former employer, TfL.

Transport for London

No-one complains about the complexity of TfL’s pricing structure.

Indeed, TfL’s ticketing system (Oyster + Contactless) is generally held to be a global role-model.

Yet, (and this is a really important point), under the bonnet, TfL’s fare structure is fiendishly complex.

To illustrate this, let me tell you about one of my favourite leisure journeys: from Walthamstow (where I live) to Richmond (the beautiful suburb in South West London, full of stately homes, parks and deer).

The following is the list of single fares between Walthamstow and Richmond.

Cash fares:

By Underground and Overground: £7.00

By Underground and National Rail: £9.90

Oyster and Contactless fares:

By Underground, Oyster or Contactless, Peak (Monday to Friday from 0630 to 0930 and from 1600 to 1900): £4.60

By Underground, Oyster or Contactless, Off Peak (All other times): £3.40

Changing between London Underground and National Rail at Waterloo (or Blackfriars, Cannon Street, Charing Cross, London Bridge, Victoria or Waterloo East) or Changing between London Underground and National Rail at Battersea Power Station/Queenstown Road or Vauxhall, Peak: £7.30

Changing between London Underground and National Rail at Waterloo (or Blackfriars, Cannon Street, Charing Cross, London Bridge, Victoria or Waterloo East) or Changing between London Underground and National Rail at Battersea Power Station/Queenstown Road or Vauxhall, Off Peak: £5.90

Avoiding Zone 1 via Highbury & Islington or Hackney Downs/Hackney Central or Avoiding Zone 1 via Blackhorse Road and Gospel Oak, Peak: £3.00

Avoiding Zone 1 via Highbury & Islington or Hackney Downs/Hackney Central or Avoiding Zone 1 via Blackhorse Road and Gospel Oak, Off Peak: £2.20As you can see, there are are only two cash fares but six different Oyster / Contactless fares!

If TfL these tickets were still sold the way rail tickets are sold, TfL would be constantly lambasted for this fiendish complexity. Imagine going to a ticket machine in Walthamstow Central station and having to choose one of these six fares, knowing that if you chose the wrong one for the journey you subsequently made, you’d risk a penalty fare or prosecution.

The reason why TfL’s ticketing is seen as a triumph not a tragedy is because there’s no cognitive effort required, nor jeopardy and the fares don’t feel arbitrary.

The lack of cognitive effort and jeopardy result from the same feature: Oyster and Contactless cards allow you to travel on all public transport in London, and the system chooses the fare based on the journey you’ve made.

That means that there’s no cognitive effort, as you simply touch in and touch out, and the system does the thinking for you. There’s also no jeopardy. TfL does employ inspectors but they will simply scan your card. As long as you have an Oyster card or Contactless card, you don’t have to fear being told you have the ‘wrong’ ticket.

Finally, the point about arbitrariness. This is more subjective but it’s important: very roughly, the fares make sense. Because of the lack of cognitive effort required, no-one needs to understand where all these various interchange points actually are or worry too much about when off peak starts and ends: they just see what’s gone out of their account.

What they see is that if they travel at rush hour, it costs a bit more. If they go through central London, it costs a bit more. If they go by mainline train not tube, it costs a bit more. The cheapest option is to go by Overground round the edge. The most expensive option is to do the fastest (tube and train through town), and the most expensive version of that is at peak time.

This doesn’t feel arbitrary. If you travelled the slow way via the Overground and got charged a tenner, you’d feel cross.

No-one needs understand the fares, if they make intuitive sense.

Switzerland

You didn’t think Switzerland wasn’t going to be my final example, did you?

EasyRide:

More than a fifth of Swiss journeys are made using EasyRide. This is an app-based system that works in the same way as Contactless: you swipe to start your journey and you swipe to end it. Between those points, the system tracks your travel by GPS and automatically geo-locates you to whatever train, tram, bus or boat you’re on. Like TfL’s system, it then charges you the cheapest fare for the rides you’ve taken at the end of the day.

Just like TfL, therefore, EasyRide eliminates both cognitive effort and jeopardy by getting the machine to do all the thinking at the end of the day and by eliminating the possibility of having the ‘wrong’ ticket. As long as you have EasyRide enabled you can turn up on the top of the Matterhorn, in the middle of Lake Luzern, on the Zurich funicular or in the restaurant of an Intercity train, and you’re good.

Now what about the actual fares? This is very interesting, as they’re hugely complex but they’re not arbitrary.

Fares in Switzerland are not simple.

Because the same system covers every transport mode (including buses), there are 24,852 places to and from which you can buy tickets, meaning 617,603,052 different origin - destination pairs.

The fare structure that makes them up is fiendishly complex. Fares in Switzerland are set both regionally and nationally. The national bit is according to an overall set of notional tariff kilometres (a set of rules based around distance, though not a simple per-km charge). Then regional transport associations can define zones, price points, discounts, pass types, and validity rules for their own tickets, but there’s an overall tariff kilometres framework that means that when national journeys are sold, the regional fares can get squished into a standardised set of fares that the customer will always recognise as making sense.

It’s not arbitrary - there is a logic to how the prices are set, and the logic is published. If you want to, you can go onto the website and wade through literally hundreds of pages of rules, codes, exemptions, tariff kilometres, boundary stations and all the other complexity that results in the final calculation for all 617 million journey opportunities.

As a result, when looking at the price a customer has been charged on EasyRide, it’s likely to make intuitive sense because while complex, it’s not arbitrary. There’s logic involved. They don’t need to understand the complexity if they don’t feel compelled to query it.

Non-Easyride tickets:

However, what about the three quarters of tickets still sold in advance.

This immediately makes things more difficult.

There’s a reason Boots (and Tesco and all retailers) don’t make you buy a ticket and then take the produce: it immediately induces the cognitive effort and jeopardy we’re keen to avoid.

If you have to pay first, you’re immediately giving the customer work in ensuring that what they’ve paid for matches what they go on to do.

While TfL have, in large part, eliminated pre-purchase, it’s harder on national systems.

So how do the Swiss reduce cognitive effort, jeopardy and arbitrariness for tickets bought in advance?

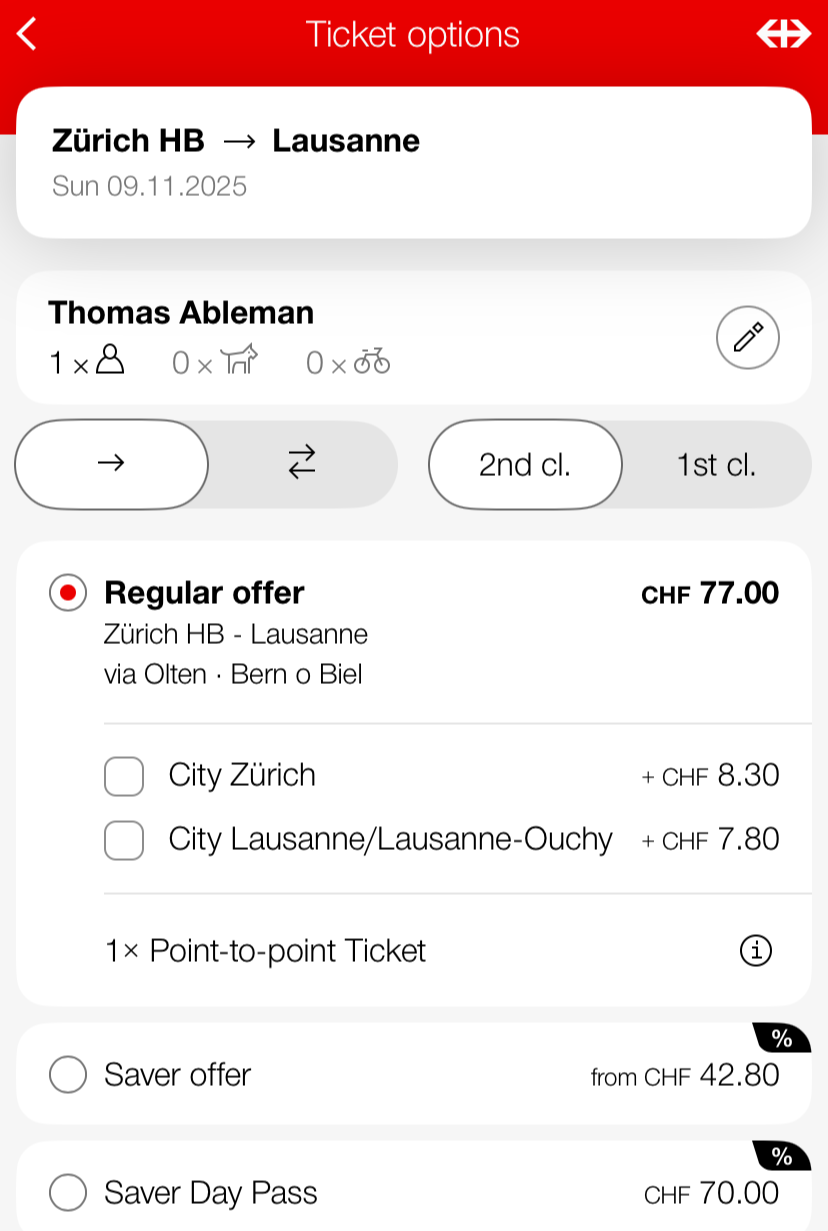

When you search for a journey on the app, you’ll only ever be shown a maximum of three options:

“Regular Offer” - the standard, refundable point-to-point ticket: always sold with a list of places you pass through and with a live list in the app of trains you can use. We’d call this the “Anytime”. This is the price comprised the fiendish complexity described above.

“Saver” - what we’d call Advance: the cheap book in advance, non-refundable ticket. This is based on revenue management and operated by SBB on behalf of the whole Swiss network.

“Day Saver” - the equivalent of what we’d call Off Peak or Super Off Peak.

But it’s very clever. Our mid-range between Peak and Off Peak has less validity than the Anytime. The Swiss equivalent has more. Off Peak is one of the biggest sources of jeopardy in our system. People are genuinely fearful about misunderstanding the timing rules. In Switzerland, there’s an Anytime and Advance (like we have) but the mid-price ticket between them is cheaper than Anytime (because it’s book in advance and non-refundable) but more expensive than Advance because it covers every train, tram, bus and boat in Switzerland. i.e. for a bit more than the cost of the Advance, you get to go literally anywhere in the whole country. No jeopardy now, is there!?

Here’s an example of a journey from Zurich to Lausanne. You can see the three options:

When you click into one of the offers, you’re also given the chance to upgrade to unlimited city urban transport in the city you start and finish from.

Now here’s an example of about the most complex journey you can imagine making in Switzerland: from Sogogno (my favourite village in the Italian-speaking Alps, accessible only by bus) to Chambésy (the suburb of Geneva in which my cousin lives):

This time, only two of the options, but the categories are familiar. There’s no upgrade to city transport in Sogogno (as it’s a tiny village) but there is for Chambésy (as it’s a suburb of Geneva).

“Ho, ho!”, I can hear you shout, “Gotcha! What you’re describing is very simple - told you the problem was complexity!”.

Soz - but I’m afraid that’s not the case.

The presentation of the fares is super-simple, with the same three options always offered for every combination of journeys in Switzerland.

But the Regular Offer is formed of the massive complexity of the fares tables meshing regional and national pricing structures that I described above. While the other two prices are calculated by revenue management computer to maximise earnings. It’s not simple.

But they’ve successfully reduced cognitive effort by always offering the same three ticket choices (even though the fares system underneath is fiendishly complex). The way they eliminate jeopardy is to only have tickets that are available on the train you’ve booked (they call Saver, we call Advance) or on every train (they call Regular, we call Anytime). But that doesn’t mean they don’t have a mid-point price (we call Off Peak, as that’s necessary for revenue management) but they make it valid literally everywhere, so there’s no jeopardy from the ticket that causes our customers the most stress.

We’ve already discussed how they eliminate arbitrariness: their hugely complex system is all tied together by a series of national tariffs that determine the overall guidelines for price per kilometre, which everyone agrees on. All the tariffs are published.

Clearly pre-purchase tickets can’t eliminate cognitive effort and jeopardy as well as EasyRide: but they have EasyRide, which - like TfL’s contactless system - completely eliminates all cognitive effort and jeopardy.

Why all this matters.

If you’re still reading (poor you!), you may be asking why the hell any of this matters.

We need less complex fares, right? JFDI!

Well, the reason it matters is that it’s possible to attempt to eliminate complexity in ways that don’t actually address the underlying problem.

Indeed, we’ve done this before.

Back in 2008, the rail industry put huge amounts of time, effort and money into simplifying fares, precisely to deal with the issue of complexity.

All the various fares that existed were swept away and replaced by just three types: Anytime, Off Peak and Advance.

A poster from the 2008 attempt to resolve fares complexity

So why, 17 years later, are we still talking about fares complexity?

Well, because while that simplification was a helpful tidying up exercise, it only dealt with complexity. As we’ve discussed, it didn’t resolve the key elements of cognitive effort, jeopardy and arbitrariness.

Resolving arbitrariness requires elements of fares reform. Our current fares system is a bugger’s muddle of the outcomes of legacy competition, fares regulation and the ghosts of British Rail. You can read more about that here.

But most of the solutions to cognitive effort and jeopardy aren’t about the actual prices: they’re much more about how they’re sold.

In this blog, I’ve not suggested specific solutions, as there are multiple ways to move in the right direction. I’d obviously love to lift ’n’ shift the entire Swiss system, but it’s taken them literally decades to get to where they are today and even if we started today, we’d also take decades to get there.

But there are two things I am saying:

We need to be hyper-cautious about talking about reducing complexity. Whenever you hear someone say that there are 55 million train fares, just remind them that there are 617 million Swiss fares - and that’s before you count a further billion that can be computer-generated by the revenue management system. Yet this isn’t an issue in Switzerland

Instead, the test for all future fares, ticketing and retail initiatives (big and small) should be to move towards the elimination of cognitive effort, jeopardy and arbitrariness. If we achieve those, complaints about complexity will vanish by themselves.

Addendum

I published a LinkedIn post last week saying that I was writing about complexity this week. Mike Lambden, retired Head of Corporate Affairs at National Express, replied with this comment:

Complexity was always there. You probably will not remember the huge library of fares manuals that staff had. However, the public never had to worry about that as the person in the booking office sorted it all for them, It was only when it got into the public domain that it seemed complex for passengers.

In one paragraph, he said what I’ve just spent the last thousand words blathering on about. (I’d already written the post, otherwise I could have just published Mike’s comment and saved us all some time).