Mobility isn’t software

Every extra byte is free

NETFLIX AND APPLE REVOLUTIONISED FILM AND MUSIC THROUGH SOFTWARE.

the economics of software and the economics of transport are very different

This is the first in two posts about “Mobility-as-a-Service”; the highly fashionable transport concept.

Almost everywhere you look, you find people saying that MaaS is going to be the saviour of public transport.

I’m going to stick my neck out and say that MaaS is (when taken literally) flawed and (when re-defined, as it often is) a distraction.

What is MaaS?

One problem with MaaS is that no-one seems entirely clear what it is. I recommend you google it and open five different reports. All start with several pages attempting to nail down the definition. That’s never a good sign. Micromobility, autonomous vehicles, open data, road pricing and other genuinely transformational solutions don’t need pages of definitions.

The reason why it’s so hard to pin down is that the original idea (which is admirably simple) is also flawed.

Rather than accept that it’s flawed and move on, proponents have then worked to reframe the idea until it reaches a place that feels like it can work. Even if that place is a long way from where the idea started.

The fatal flaw

Mobility-as-a-Service started out with the simple idea of replicating the success of Software-as-a-Service.

Software-as-a-Service has been one of the great tech success stories of recent decades, in which a whole bunch of different products that previously had to be bought as one-offs can now be accessed via simple monthly subscriptions.

Once upon a time, you needed to rent films individually. Now you just pay for a monthly Netflix subscription.

Once upon a time, you needed to buy a finance system. Now you just pay for a monthly Xero subscription.

Once upon a time, you needed to buy singles. Now you just pay for a monthly Spotify subscripton.

At one point in the early 2010s, some smart-alec said “Why can’t mobility be like Spotify? With Spotify, you pay one monthly subscription for all the music you want. Why can’t you just pay for one monthly subscription for all the transport you want?”

That is the true definition of MaaS.

And it’s a brilliant idea. Genuinely. Consumers would love it, and if it ever happened, it would revolutionise transport.

But in this article I’m going to point out that much of it is already happening (e.g. the Travelcard) and the bits that aren’t happening are almost impossible to achieve.

This is because this original idea of MaaS is based on a fundamental misunderstanding, as mobility is not software.

The reason SaaS has taken off is that cloud computing combined combined with universal broadband has enabled multiple additional service users to access software without materially increasing the central costs of delivering that software. Once a piece of software is created and uploaded to the cloud, it is almost free to go from 2 users to 200,000 users. In such a situation, simple low pricing bundles are the obvious way to incentivise rapid growth as every additional user is virtually free to serve.

Software services such as Spotify, Stripe, Xero and thousands of others all work in this way.

But mobility does not share this foundational characteristic of all SaaS businesses: the incremental additional user is not almost free to serve.

The incremental user of a mobility solution can be almost free. The 50th passenger on a bus with 50 seats is free to serve. But the 51st is phenomenally expensive to serve. Taxi rides incur fuel and labour costs in proportion to custom. Shared bike rides create an opportunity cost, as when person A is riding a bike, they are preventing person B from doing so.

None of these things are true with software in the environment of cheap data plans and cheap cloud computing.

Much of the excitement around MaaS is based on the fact that SaaS solutions have made things that had previously been complex and expensive become simple and cheap. Transport commentators repeatedly justify the hype for MaaS by saying that transport will be transformed ‘like the way we buy music has been transformed’. Or they quote Netflix and say MaaS will do for mobility what Netflix has done for TV.

But these commentators fundamentally misunderstand why these transformations happened. Netflix and Apple Music are based on technology that made incremental users free. The transformation of the music industry was caused when CDs (incremental user costly) was replaced by digital downloads (incremental user free). Netflix can offer a subscription for unlimited films only because the cost of streaming each film is effectively free. Indeed, Netflix (who spend billions of dollars making the programmes) have a huge incentive to then attract as many subscribers against which to offset that cost. That does not apply to DVD's and Netflix’s DVD rental service in America (yes, they still have one!) does not allow unlimited viewing, as DVDs are physical and have an incremental cost.

The point about SaaS is the bundle price is calibrated to be good value for a typical user. A hyper-user will get outstanding value but that’s cool, as they don’t add to the costs through their gargantuan consumption.

If we applied these principles to mobility, we’d start by looking at a typical user, and creating a base subscription to pull them in.

We know that the typical Londoner makes 0.2 tube trips and 0.3 bus trips per day. So roughly 15 trips per month. Let’s assume the average fare paid is about £2 (I suspect it’s somewhat lower, given the large proportion of bus journeys, but it doesn’t make much difference). As we want to price for a typical user, that means lead-in pricing tier should be £30 per month for an all-you-can eat London subscription. In SaaS world this low price is great, as it’s highly likely to pull in lots of additional custom. Yet, it’s only about the a sixth of the price TfL actually charges. Why?

In a SaaS world, a low price for an all-you-can-eat service is fine - the margins are still phenomenally high per user and you generate more users than you would from a high price - without materially increasing your opex. But for TfL, a £30 monthly subscription would only work if all the people who only do one or two trips per month would be willing to pay £30 (a huge price increase) to balance the daily commuter who’s just had their fare reduced by around 85%.

It may be that they would. That’s the point of Netflix - people watch more films streaming than they did on DVD. But, of course, the reality is that these infrequent travellers would now be incentivised to use the service a lot more. Which means more capacity would be required, which increases costs…

None of these dynamics affect a SaaS business.

And, of course, my illustration was based purely on bus and tube journeys. But part of the attraction of MaaS is that it covers all modes, fully flexibly. If we assume that the average Londoner spends £10 per month on taxis, then we could do a £40 subscription including taxis.

Well, fairly obviously, this isn’t going to stack up. Now I’ve spent £40 on a taxi subscription, I’m going to use taxis everywhere and there’ll be insufficient in the kitty to pay the cabbie. Remember, the reason for the SaaS revolution in enterprise software is that each incremental use is almost free to serve. Taxis are the perfect mirror image: every incremental use has to be paid for in almost perfect proportion.

Mobility isn’t software and the pretence that it can be treated in the same way is causing us to look for pots of gold at the end of the wrong rainbow.

Other “as-a-service” examples

Let me give two other industry examples by way of illustration.

The first is retail. Online retail has been transformed through SaaS. Over 1,000,000 individual businesses use the SaaS platform Shopify for their online retailing. Shopify works like all SaaS platforms, with simple, low subscriptions - fuelling massive growth.

But this is because it is online retail, so the rules of software apply. Just as transport has driven itself into the MaaS dead-end, so the world of physical retail has tried to invent RaaS (Retail as a Service). And, of course, despite years of trying, it simply hasn’t worked because servicing each incremental user is not free in a physical shop, just like it’s not for any transport product. (To see what this retail dead-end looks like, check out B8ta, who are valiantly attempting to make RaaS a thing).

So if we can’t do an all-you-can-eat subscription for all transport modes, what can we do?

Well, Pret shows the way here. They are currently proving that great value subscriptions for specific products can work in the physical world.

Pret has recently started selling coffee subscriptions - £20 flat price for as many coffees as you can drink. Even though each coffee brings its own cost, they judge that most people won’t drink so many that the incremental coffee cost exceeds the income. That’s why they’ve done it for coffee (which is very low cost to make - as close as you can get to software in the real world) and not sandwiches (which are individually expensive - more like a cab ride). Also, they haven’t done the SaaS thing of only selling subscriptions - they still sell individual coffees but the subscription is an overlay.

There’s a reason they don’t have a sandwich subscription…

So, what does that tell us? In the physical world, we can do a monthly subscription but only for the products with a low incremental cost and always combined with also selling individual unit prices.

So that means offering a subscription to mass transit (such as bus or tube) where each incremental user is virtually free until you hit capacity, but not things like taxis where each trip is paid for individually. And like Pret, we’ll keep selling individual unit prices (i.e. single fares) but also offer a monthly subscription price over the top. So while we’re not going to have a single low price for universal access to all forms of mobility, we can have a subscription price designed to offer good value to an intensive user of a specific service. Which is great… but we’ve just invented the season ticket.

The reality is that “as-a-Service” solutions don’t work for physical goods with their own incremental costs.

MaaS in the real world

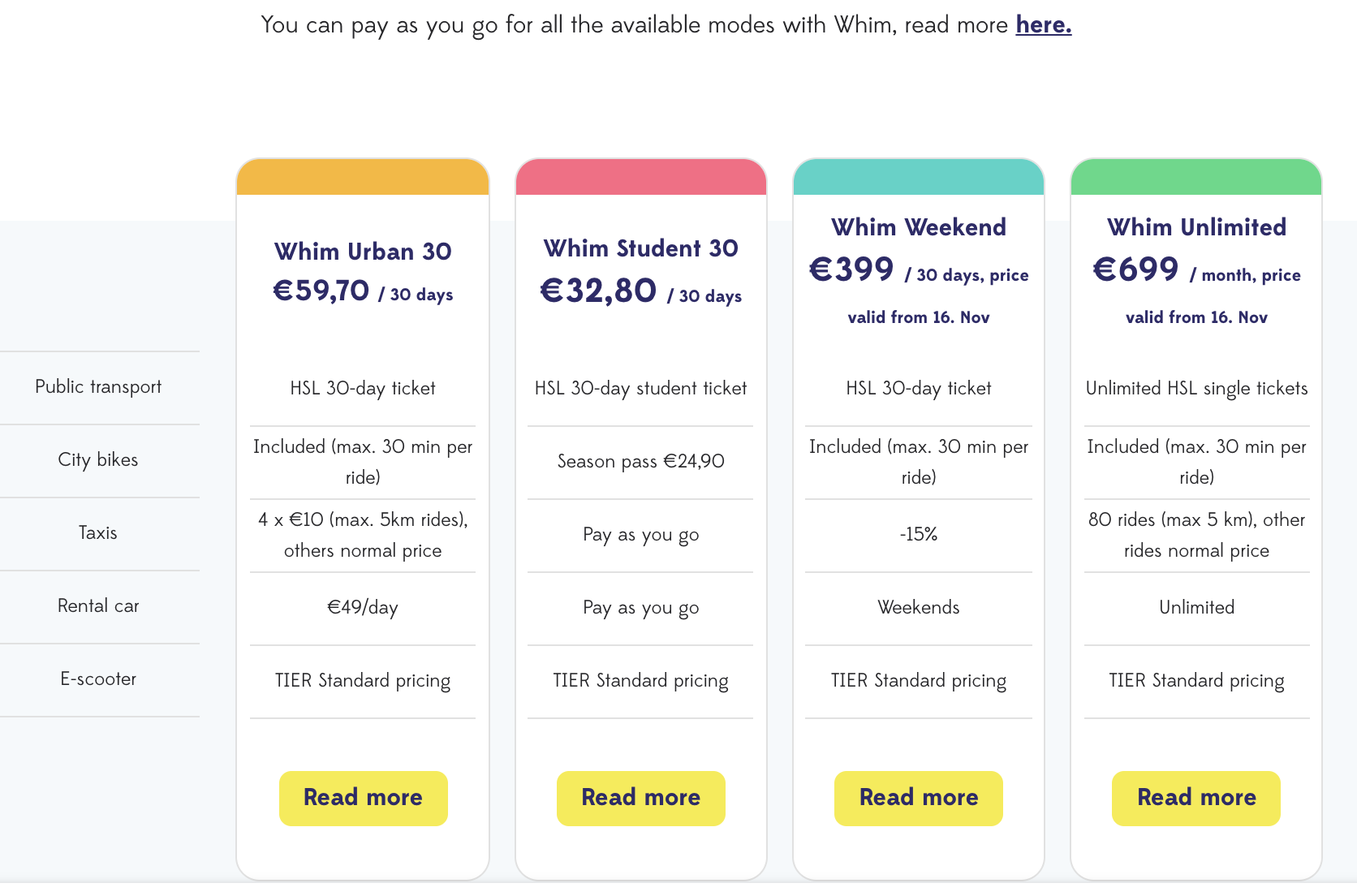

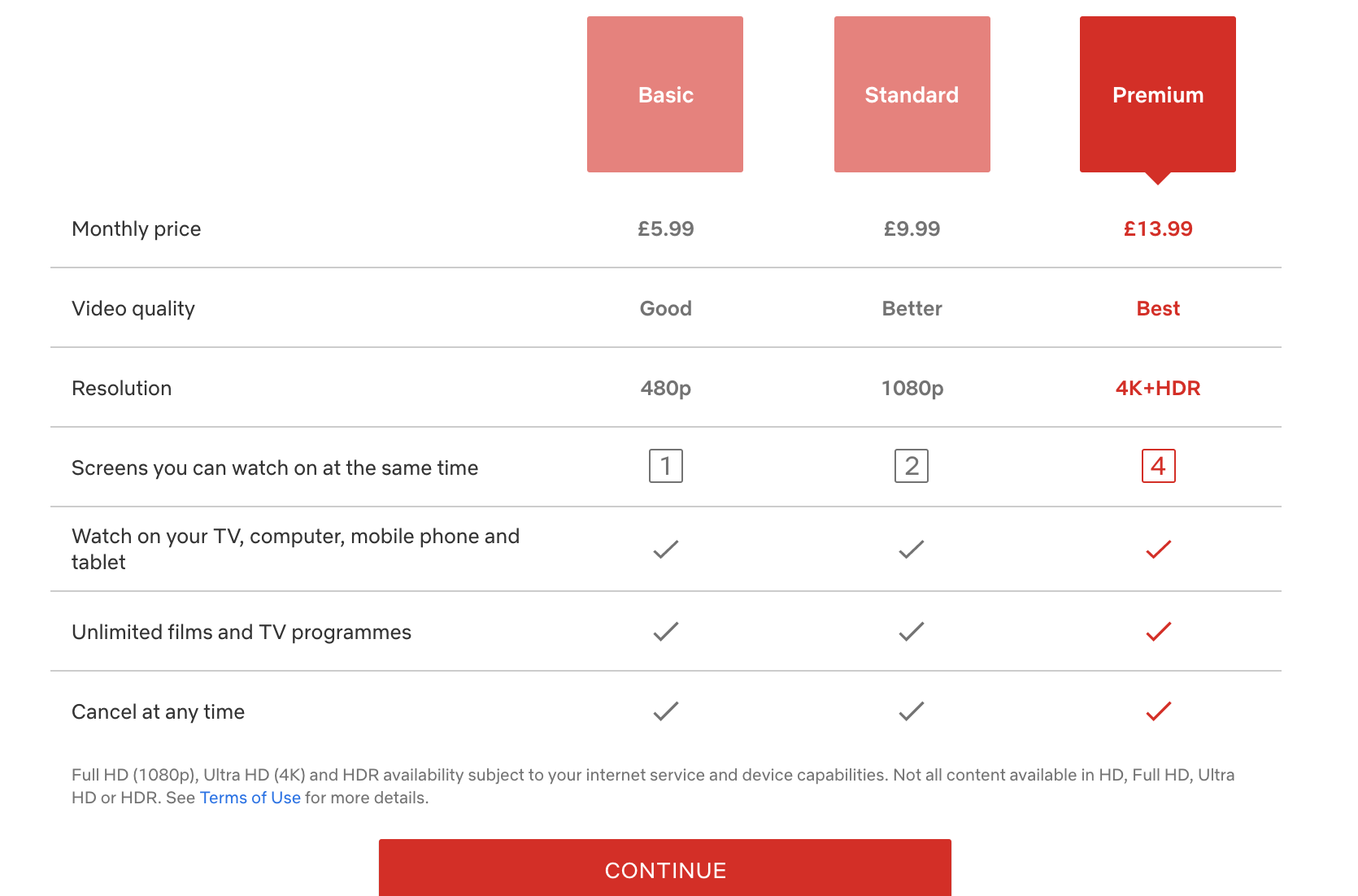

We should already know this as the only MaaS service that anyone talks about with enthusiasm is Whim in Helskinki - and it isn’t anything that the world of SaaS would recognise. Let’s compare and contrast the Whim pricing page with the Netflix pricing page, and you’ll see what I mean.

Whim’s pricing bands are a mess of extra prices, limitations and percentage discounts. Even the “Unlimited” bundle requires you to pay extra for e-scooters and some taxi and bike rides. By contrast, Netflix offers three simple bundles, all of which include unlimited films.

By the way, I think the Whim product is good and I wish London did something similar. It doesn’t feel like it should be impossible for TfL to wrap up the first 30 mins of some bike rides into a travelcard, and a small discount on four cab rides would be a sensible deal for LTDA to do commercially (though I can’t see it happening!).

But the reality is that Whim is much closer to the existing Travelcard product than it is to any SaaS product.

So the good news is that if Whim in Helsinki is MaaS, then it already exists in every major city.

Which is great.

As we can all stop talking about it!

Next week I’ll talk about why the fact we don’t stop talking about it is a “MaaSive distraction”.