Are part-time season tickets an unnecessary bung for the already rich?

It’s universally agreed that we should have part-time season tickets. But we shouldn’t.

The new office two days per week?

I keep reading about flexible or part-time season tickets.

Everyone seems to agree that they’re a marvellous idea and must happen as quickly as possible.

But I’m not totally sure that the people arguing for them have actually thought through the implications.

Season tickets make sense

Because the delivery mechanism for season tickets is somewhat antiquated, there is a tendency to see them as old-fashioned.

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve heard someone talk about the ‘traditional’ season ticket.

But season tickets are the inevitable result of an operating model in which most costs are fixed, and the cost of the marginal user is very low.

In that regard, railways have a lot in common with Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) businesses, in which up-front investment is made in the creation of the platform, but distributing to additional users is cheap.

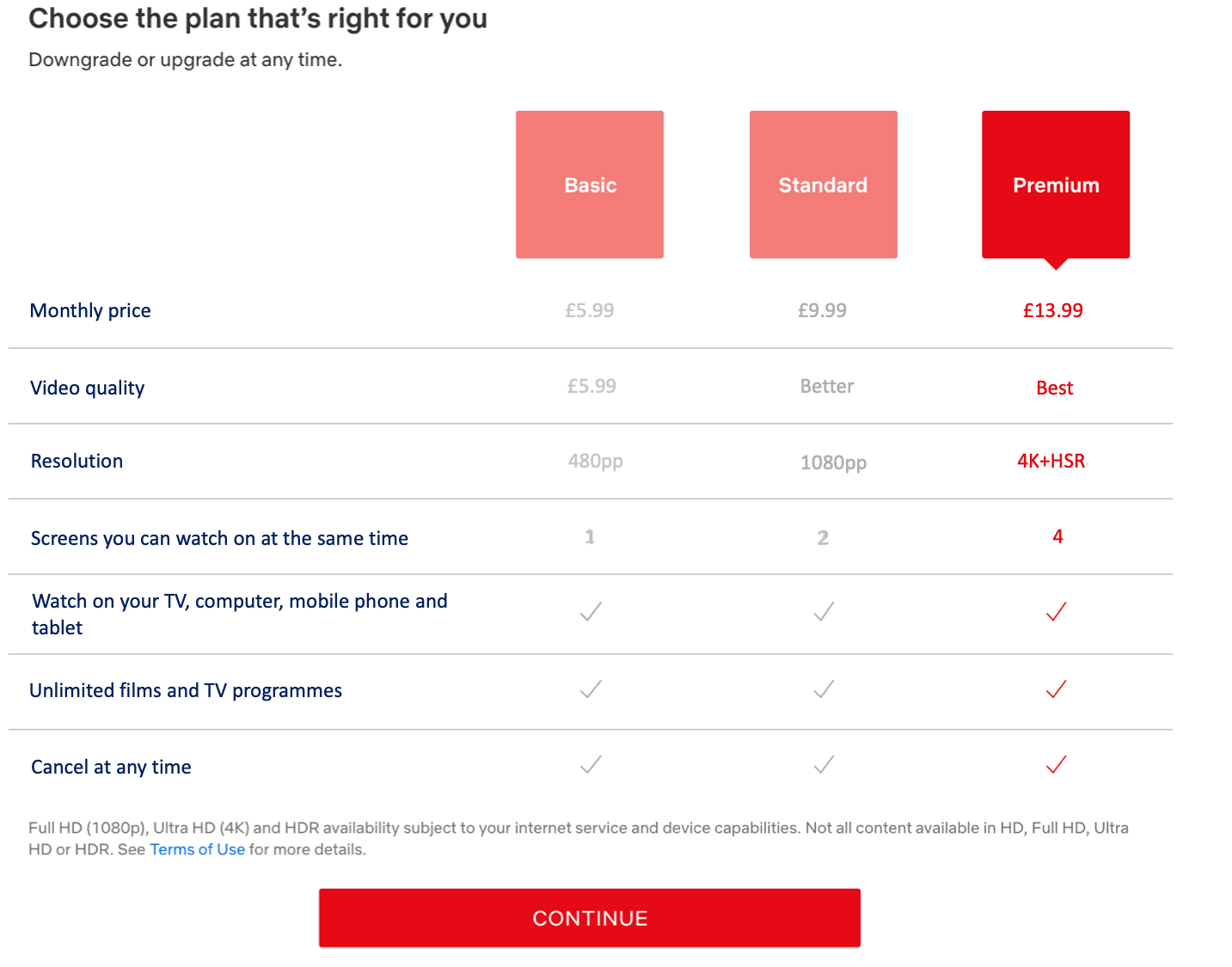

If you look at Netflix, all three pricing plans allow unlimited films and TV shows.

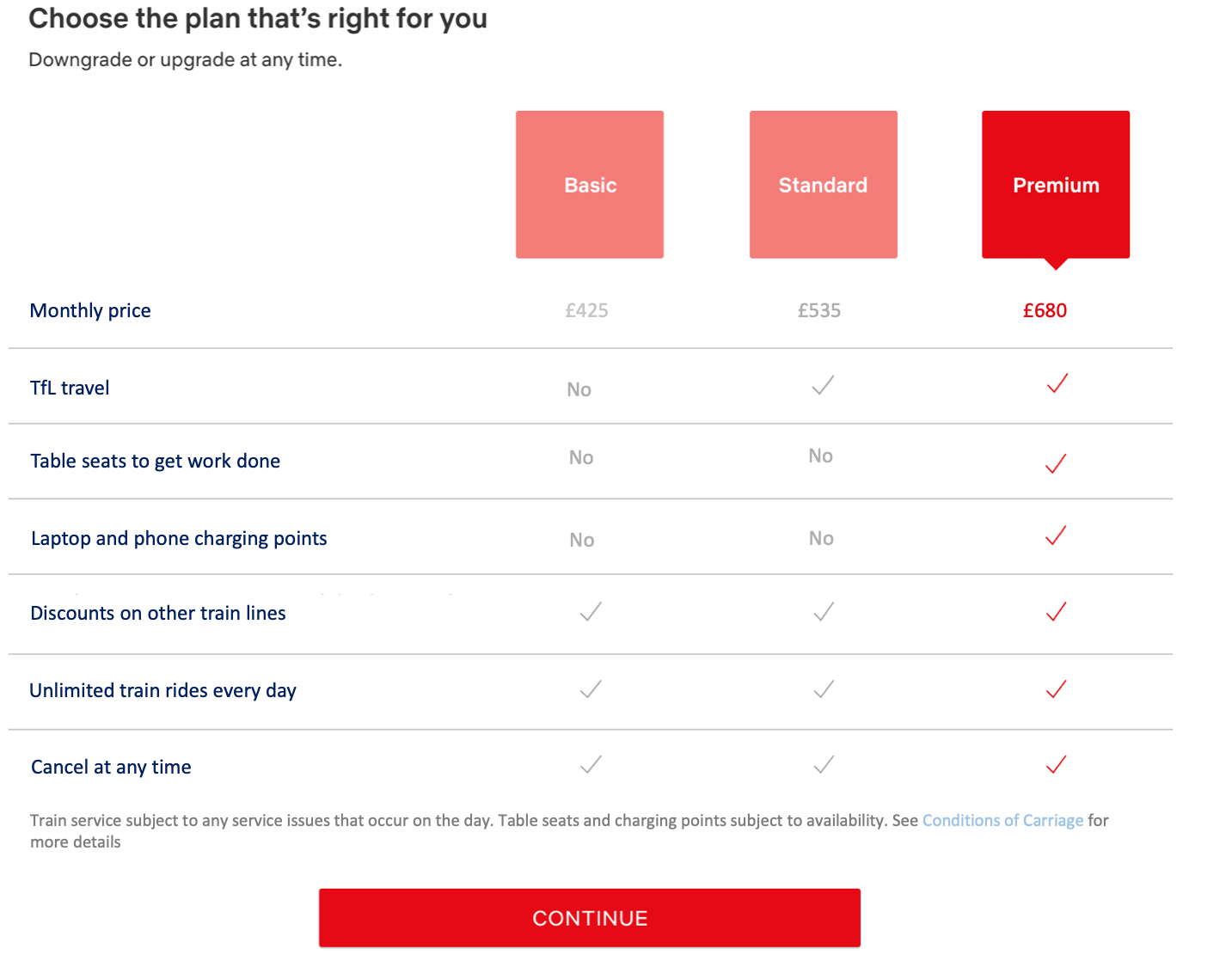

Indeed, it’s interesting to present a rail season ticket as if it were a SaaS style product.

Here’s Netflix’s UK subscription page and, for comparison, the season tickets from Luton to London, as would be presented by Netflix:

Once we realise that a season ticket (yah, boo, old-fashioned) is the same as a subscription (modern, current, the way forward), then we can do the thought experiment as to how Netflix would think about part-time season tickets.

What would Netflix do?

So a bit like we know that, before the pandemic, a typical Rail subscriber (let’s call them that) used to do around 40 rides per month, so survey data tells us that a typical Netflix user watched 35 shows per month. That meant that, just as a season ticket holder gets a great deal on their rail travel, so do frequent users of Netflix.

Now, I am clearly not a typical Netflix subscriber - with two children, a startup, a blog and a podcast to run (listed in order of time they consume…), I probably watched just one show per week, meaning that my average show cost £2.40; nearly 10 times the average.

I cancelled.

I judged Netflix would not have responded enthusiastically to my request to pay 30p per show like everyone else, and allow me to pay just £1.20.

This applies to every SaaS service: I stream less on Spotify than average (I find music essential to financial modelling work but a distraction to written work and don’t like listening to music out of the house), but Spotify will not let me pay the average user price for a song.

Nor, so far, has the railway.

But what we’re told is that the collapse in demand for rail travel fundamentally changes things, meaning that now is the critical moment for part-time season tickets.

So, let’s imagine that demand for video streaming or music collapsed for some reason. (Maybe the the Royal family successfully sue for defamation, and everything on Netflix has to be true from now on…)

How would Netflix respond?

Well, they would recognise that their core business model remains the same: the content involves massive up-front expenditure and each incremental user is free. So they will still want to pitch the price point at a level where it becomes a no-brainer for a typical user. If the typical user now wants less, then they’ll probably lower the subscription price point. This will bring in some users that were previously marginal, at the cost of making it even cheaper for a handful of super-users at the top.

A tedious illustration with lots of numbers

I’m now going to get into a series of illustrations to make my point. If you like, you can skip this bit and jump straight to the conclusion. You’ll find it just below a big picture of a coffee cup.

For clarity, everything here is made up, as I have no idea what Netflix’s market data looks like. But it’s probably vaguely sensible.

I’m going to assume that of the 5bn internet users globally, around 200m can afford Netflix today, a further 100m could afford it if the price fell a bit and another 100m if it fell a bit further.

For the majority of global internet users, Netflix is an unaffordable luxury. In terms of demand for shows, I’m going to assume that the current average of 35 sits at the centre of an approximate standard distribution.

So you end up with a table that looks somewhat like this, with the green representing the current 200m Netflix subscribers. These are the people for whom Netflix is affordable and who want enough shows that it’s worth paying for Netflix. To calculate the green, I’ve made the assumption that people will be willing to pay for Netflix if each show - for them - costs less than £1.

The unit of data in this table is millions of users. So, for example, the number “48” means there are 48 million people in the world who want to watch 20-30 shows a month and can afford Netflix.

Making the assumption that people will only be willing to pay for Netflix if each show costs £1 or less, this means that the group of people highlighted in green will become Netflix subscribers. This 199 million people are rich enough to afford Netflix, and their usage is high enough to justify it. It’s worth noting that while the marginal user is paying £1 per show, the typical user is paying just 30p and there is a cohort of super-users that are getting shows for less than 20p. Yet Netflix charges a single subscription or ‘season ticket’ as you might call it.

Like a season ticket, it is segmented by geography (Netflix in Pakistan is a lot cheaper than Netflix in the UK) but it is not segmented by the number of shows a user streams.

OK, so let’s imagine that we all go off the Crown, and demand falls through the floor. This is analogous to the situation that many of us think the railways will be facing post-Covid.

For simplicity, in this scenario, the number of shows watched by the typical use is going to halve, and users are not going to be willing to pay unless shows cost less than 50p per show.

The result on Netflix’s revenue would, of course, be catastrophic:

Total subscribers would fall to 63 million, with revenue falling to just under £630 million; around a third of the base.

This is approximately the position that many people are worried that railway commuting is about to face: high fixed costs but a demand collapse driven by a reduction in the amount that people wish to consume on a monthly (weekly) basis, making the subscription no longer feel like good value.

The idea, therefore, is that a new lower priced tier is created, which buys a smaller bundle of trips.

So let’s see how this looks for Netflix.

Let’s imagine that Netflix say, “OK, if you want fewer than 20 shows per month, we’ll give you a new £7 subscription. But if you want more than 20 shows, you continue to pay £10”

On the table below, therefore, the group of people continuing to pay £10 is marked in green.

In orange you see the people now paying the new £7 subscription. The good news is that this £7 price point is accessible to people that previously could not have afforded Netflix. That’s why the orange block extends onto the row below:

So this is quite exciting! What we find is that the new lower price point, by bringing new people into scope for Netflix, has brought revenue back to where it was before the demand fall. Problem solved! The part-time season ticket idea is brilliant!

Except……. what is interesting is that we didn’t actually need to create a separate pricing tier to achieve this. Here’s what it would have looked like if we had simply cut the subscription to £7:

By offering the lower price point across all demand levels, we bring new demand in from across the market segment that, previously, could not quite afford Netflix. Even though 63 million people are going to be paying less than they’d be willing to pay, we benefit from 31 million people that otherwise would have paid nothing at all. The entire subscriptions of the 31 million exceeds the increment for the 63 million.

The result is that all the effort and complexity that Netflix might have gone to in order to create the extra pricing tier was unnecessary.

They just needed to keep a simple subscription model, but cut prices in order to react to the fall in demand.

So, we have an answer, a new low cost, low use pricing tier for Netflix is kinda pointless but also kinda harmless.

Applying this learning back to rail, we’d conclude that:

If demand collapses, we need a big price cut

A price cut might actually bring in sufficient new users to mitigate the impact of the price cut

A new low usage pricing tier is unlikely to bring in new revenue, but unlikely to do any harm.

And this would all be true. However, there’s one very important point.

What we’ve been looking at here is how Netflix can maximise their earnings.

But the goal of part-time season tickets as stated is not to maximise earnings but to ensure that part-time workers pay the same per trip as full time workers. This is the equivalent of me wanting to phone Netflix and ask to pay £1.20 not £10 because other people are paying 30p per show.

So let’s imagine how this would apply to the Netflix scenario.

Originally, a typical Netflix user was paying 30p per show (35 shows p/month, £10 per month)

A marginal Netflix user was paying £1 per show (1o shows p/month, £10 per month)

Our goal is that all Netflix users get to pay 30p per show.

But at the new, reduced price point of £7, a 10 show user is now paying 70p per show; still double the rate paid by our 35 show user.

Let’s imagine we, therefore, engineer the pricing to ensure that a 10 show user gets to watch shows at 30p per show.

This is the scenario most people are talking about when they talk about a part-time season ticket. Keeping the existing season ticket for the existing market but introducing a new lower priced season ticket that is limited in the number of trips that it buys.

We can achieve this objective for Netflix by introducing a £3 subscription for low users:

Low users now get to watch Netflix as the same price per show as high users. This crazy low price also brings in another layer of market demand; the 100 million people currently unable to afford Netflix. Netflix users skyrocket, but the effect on Netflix’s revenue is catastrophic. It’s a quarter down on where it would otherwise have been.

Moreover, once again, we didn’t actually need to introduce the lower usage tier to achieve this. Had we simply cut the subscription to £3, we’d have achieved the same goal at the same loss of revenue:

Once again, the complexity of introducing a dual price point structure has turned out to be pointless.

If there’s a desire to make Netflix more affordable (at the expense of income), the way to do it is simply to cut the price.

Lessons from Netflix

First thing first, let’s stop talking about ‘traditional’ season tickets as if they’re a legacy problem. As Netflix shows, a subscription model is entirely modern for a high fixed cost business with low cost of onboarding marginal customers.

Indeed, there’s a reason why Pret have just introduced coffee subscriptions but not sandwich subscriptions. Coffee is the product with by far the lowest marginal cost of incremental production.

Call it a subscription and it becomes modern

So the key lessons we can take from this thought experiment are:

If commuters want fewer journeys post-Covid, there’s no benefit to introducing a new part-time season ticket. But there is probably a benefit in cutting prices for everyone.

Low usage subscriptions create complexity without much benefit. That’s why many SaaS businesses don’t have them.

Making fares for part-time workers as cheap per journey as fares for full-time workers will reduce income, as it is giving a bulk discount to people who don’t buy bulk.

On that latter bullet point, there may be a political desire to achieve this. And if there is, then it will happen.

But the DfT needs to be honest that it is a fare cut for rail commuters, that will increase the need for subsidy.

And we know that rail commuters tend to be richer than average - and long-distance commuters richer still.

Part-time workers will sometimes be poorer than average (even taking into account the fact that rail commuters, overall, are wealthier); but many will be the partners of full-time workers from affluent households.

Cutting their fares might be a popular move.

But it also means that taxpayers nationally will be paying more to subsidise families who live, overwhelmingly, in the more affluent parts of the country and typically have higher than average household incomes - often making it easier for these families to reduce their housing costs by living further out in the commuter belt.