Should we cut fares?

Last year I wrote a post explaining why free fares are - basically - a bad idea.

Today I’m putting my head in the lion’s mouth by explaining that, not only should we not make fares free, we shouldn’t even make them substantially cheaper.

I realise you’re going to shout at me.

But do remember that I almost certainly use public transport more than you (and have no passes), so I’m arguing away something that would benefit me personally a lot.

But there is a very simple reason why public transport fares shouldn’t be lower: there are only two sources of funding for public transport: farepayers and taxpayers.

For the foreseeable future, access to taxpayers’ cash is going to be more competitive than an Olympic 100m sprint, so if we’re going to continue to invest, fares need to stay high.

You’re having a laffer

There are several arguments for cutting fares.

One is that fares are subject to a kind of Laffer curve, in which lower fares will generate higher revenue.

Arthur Laffer, inventor of the Laffer curve. He convinced Ronald Reagan that cutting taxes would increase revenue. At that point, US national debt was 40% of GDP and had been falling almost continuously since World War Two. Today, it’s around 100% of GDP and has been rising almost continuously since Reagan’s tax cuts.

(The Laffer curve, for those who don’t know the name of Liz Truss’s national economy-killing experiment, is the idea that cutting taxes will increase Government tax revenue.

It’s true at exceptionally high tax rates, as a 100% income tax would prevent anyone working, so a cut would obviously increase revenue. But at mainstream rates, it’s basically bollocks.

Which is what the Bond markets told Liz Truss in no uncertain terms.)

Now, the idea that lower fares can generate higher revenues can be true.

Indeed, Ryanair have built the biggest airline in Europe through that insight.

But circumstances in which finding the economic fare (i.e. the fare that maximises revenue) requires a cut tends only to be true in circumstances of intense competition.

When large numbers of people have already decided to travel from A to B, then it’s easy to tempt them en masse to switch from one provider to another through the provision of lower fares. Especially when the entity cutting fares is, otherwise, inferior.

Like Ryanair…

I’ve personal experience of this. I spent a fascinating year as commercial director of the open-access rail startup Wrexham & Shropshire.

When I joined, the business was struggling desperately, with costs exceeding revenue by 100%. The problem was that it was both cheaper and quicker to drive to Stafford and travel on a cheap Virgin Trains advance fare. I slashed our fares, and revenue went up. In the nine months I was there, we increased passenger numbers by 88% and revenue by 29%.

(The mathematically-minded of you will observe that this was not enough to cover our costs: the business folded two years later).

There are other circumstances in which fares end up artificially too high: often as a result of regulatory interference. I have an obsession with Holmwood, as long-time readers will know.

Many (pre-£3 cap) bus fares are higher than the economic rate as operators have jacked up the headline fare in order to maximise concessionary reimbursement rates.

These are distortions that could be fixed.

But the transport Laffer curve idea is often used to refer to cuts in mainstream fares.

The idea is that you cut fares but so many more people travel as a result that the overall income is higher.

It sounds too good to be true.

It is.

I’m afraid, there’s just no evidence it’s true.

Enough fare cuts have been made that we can be pretty confident what will happen.

Fare cuts will generally increase demand a bit.

But not enough to pay for themselves.

Equality

Another reason for cutting fares is the equality impact. The impact of high transport costs falls disproportionately on the poor, who spend a higher proportion of their income on getting to work.

For this reason, it’s surely right that fares should be lower?

Well, maybe. Intuitively, holding down fares helps the poorest, so we should do it.

However, we should also think very carefully about whether transport fares are the right vehicle to use to achieve this.

If lower fares are compensated for by higher taxpayer subsidy (though this is unlikely in the current climate) then fares are a very inefficient way of achieving this goal.

Far better that the taxpayer subsidy is withheld, and the tax credit system is used to deliver cash directly into the pockets of those who need it.

For the poorest, that has the same impact on family finances as a fare cut but ensures the transport firm’s fares are still be paid by people like me who can afford it.

If, however, the lower fares are not accompanied by an increased subsidy (which is more likely), then lower fares mean less public transport. And, as the perennial debate about levelling up (or whatever it’s now called) reminds us, it is the absence of transport that is one of the greatest causes of poverty (in general, places with worse connections tend to have lower incomes).

So if we want to level up, we need to pay for public transport - and this means fares.

Doesn’t even work

The final reason not to cut fares is that it doesn’t even achieve the mode shift goals that are key to addressing the climate emergency. Last year Centre for Cities published a report called Gear Shift, looking at different ways to increase public transport use.

They were, as you’d expect, pretty positive about bus priority measures, restraint on car use and various other things you can probably guess.

But anyone expecting a full-throated endorsement of fare cuts would be disappointed.

Evaluating places where it has been tried led them to conclude that it is expensive (Germany’s famous €9 ticket scheme cost around €2.5 billion to implement), doesn’t encourage modal shift (even in places where public transport use went up, car use did not go down) and causes capacity challenges (which necessitates additional investments that are now even further out of financial reach).

I want lower fares!!

I suspect there will be some readers to this who may (or may not) accept my arguments that cutting fares won’t increase revenue and that there are better ways of achieving social equality and mode shift.

But - at the end of it - they’ll still be left thinking “BUT I WANT LOWER FARES”.

Well, so do I!

I have two children, one of whom is still financially dependent but - because she’s 16 - is considered an adult. A relatively simple day trip to the coast from London now often costs £100.

Or would if we did it.

But we don’t - because the fares are so high.

So I’m absolutely in the market for lower fares at a personal level.

And because so many of us want lower fares, we may get them.

DfT have written into the Railways Bill the right for the Secretary of State to control fares, so she might cut them for political reasons.

But this post argues that while it may be popular, it may not achieve any wider benefits beyond being popular.

The 1937-8 London Transport staff briefings book. 144 pages of detailed essays.

The Theory of Fares

Back in the 1930s, a London Transport staff briefing consisted not of a short PowerPoint decks but a 150-page paperback book of long-form essays from departmental managers.

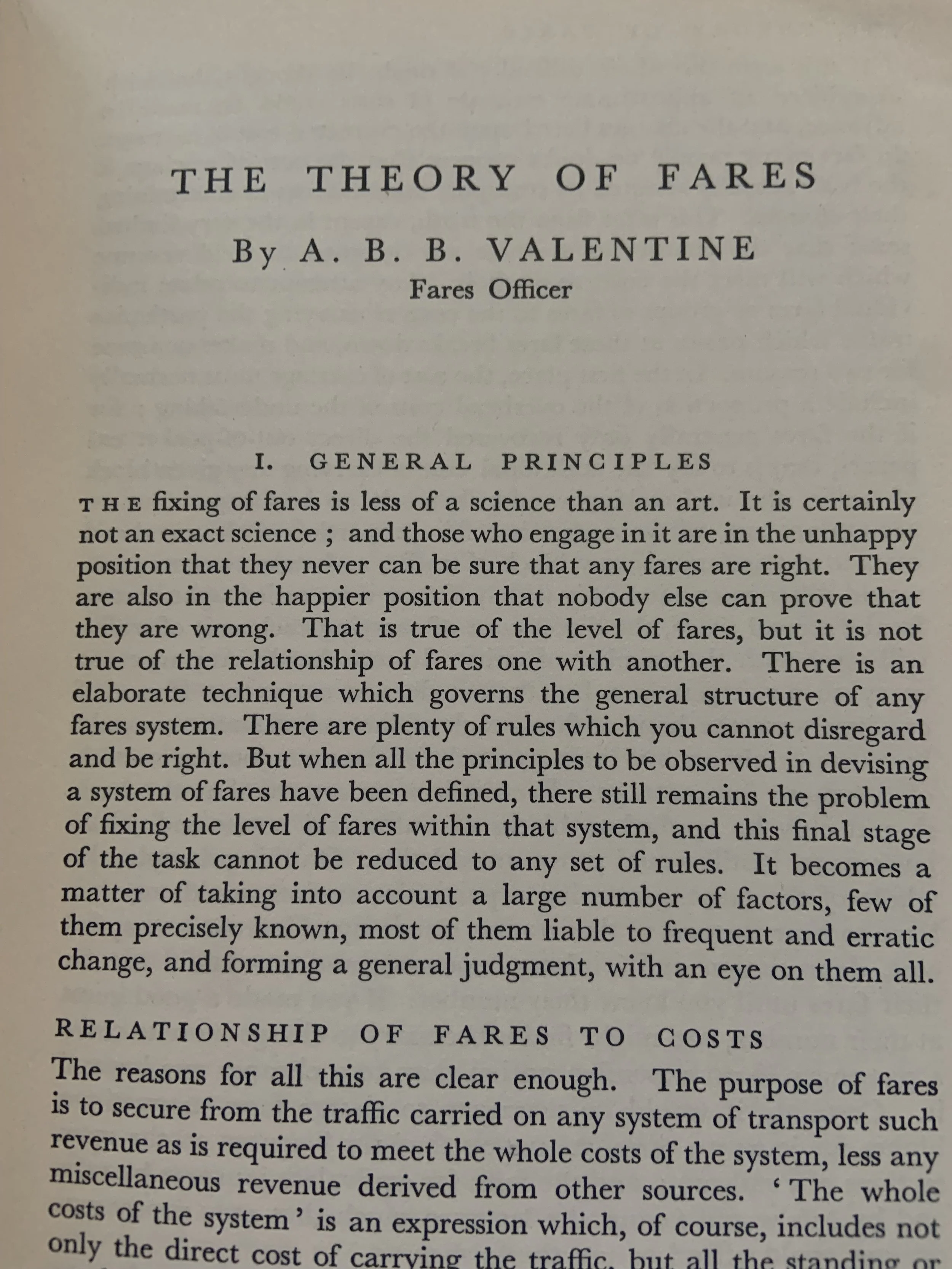

Here (below) is page one of the essay The Theory of Fares by ABB Valentine, London Transport’s Fares Officer.

A lot has changed in the intervening century, but the fundamental points on this page haven’t altered significantly.

One of the most important, though, is the point that the “purpose of fares is to secure from the traffic carried on any system of transport such revenue as is required to meet the whole costs of the system”

Page 1 of ABB Valentine’s the Theory of Fares

This is still true today, even if we also tend to forget it. Fares are primarily there to pay for the service. More fares = more service. Less fares = less service. If you think service is good, we need higher fares.

That means that passengers need to be willing to pay those higher fares. And for that to be true, the service needs to be good.

My former employer, National Express, ran the West Midlands bus network into the ground on quality, with the result that it struggled to justify fare increases. By contrast, operators like Trent Barton and Brighton & Hove were able to maintain revenue growth through both fares and passenger numbers, by offering a quality people were willing to pay for. This becomes a virtuous circle.

Don’t be stupid

Now, please don’t interpret all this in a purist way.

I’m not saying that fares should never be cut.

Far from it.

Transport companies should constantly experiment to find the optimal fare. I’ve noticed a LinkedIn hobby recently of photographing empty Avanti trains northbound in the AM peak, saying its ridiculous that the fares are high and the trains are empty. I’ve certainly experienced very lightly loaded Avanti trains at that time and in that direction. I’ve not done enough analysis to know whether cuts would generate more revenue but it’s very possible. I’m not saying no fares should be lower - many should be.

But in most places at the moment, fares are still not so high that cutting them would generate more revenue.

And that means that, with regret, they should stay high.