How to Get Government Moving Again

The Civil Service is stuck in a culture of pushing paper up to Ministers, allowing the paper to fester on Ministers’ Desks for months on end, and then be passed back down again to where it can be executed.

Often things have changed by the time it finally gets back to the official who needs it, so the whole process has to start again.

It’s no wonder that Government feels slow.

Last week, we discussed that a key reason for this is a catastrophic misunderstanding of the way decisions are taken in Whitehall that has resulted in the widespread notion that “Advisers advise and Ministers decide”.

I won’t repeat the argument from last week here (though you can read it if you want to), but the summary is: that’s just not true.

The Civil Service does not need to feel dramatically different to a private company, in which decisions are made by the person with the relevant knowledge and expertise, in real time.

But the “advisers advise” culture is well-established, so what can we do to change it?

Here are a dozen ideas to get you started.

1) State that it’s bollocks

This is actually hugely important.

If you do a ChatGPT query about “Advisers advise and ministers decide”, this is what you get:

As I explained last week, it’s just not true.

But it’s become so widespread in our thinking that the professional plagiarism machine that is ChatGPT regurgitates back to you the direct opposite of the reality.

Officials who want more accountability for decisions need to be very clear with both their Ministers and their bosses that the law is on their side. If I explain why, I’ll be in danger of repeating last week’s blog post, but read it yourself and then quote it whenever you’re challenged.

2) Make decisions Through Experiment

A view has emerged in Whitehall that “a decision” is a procedural event, and that a decision can only be seen to have been taken correctly if it was taken by a Minister and recorded in a formal memo.

But the law doesn’t care how a decision was taken, only that it was lawful, rational and fair.

Let us imagine, for example, that an official decided that - instead of commissioning a big piece of analysis and putting the conclusions in front of the Minister - they were going to fund a dozen experiments in the real world, and then scale up those that best achieved the Minister’s objectives. In this situation, the decision-making process would not have a single decision-making 'moment' but instead be a constant, iterative learning process.

Would a Judicial Review consider that the decision was made correctly?

Well, the official in question is competent to run these experiments and is doing so with the authority of the Minister. The process shows a rational connection between evidence and action. The biggest issue is that “fair” has come to be synonymous with “following a previously defined process”. So it would make sense for the official to publish a new version of this process before starting out.

Even better, the Department could publish that live experiments were now a decision-making method that the Department was going to use, thus enabling not just this official but every official.

3) Build a culture of delegation and accountability

Now that we all understand that Ministers don’t have to decide and that officials aren’t limited to merely advising, we can get on with the important work of getting decisions to the level where they make sense.

If there’s an official who understands the Minister’s goals and understands the subject at hand, they’re perfectly competent to decide.

Indeed, they should be deciding. Currently, officials and ministers are almost conspiring together to get bad outcomes, with officials (sometimes) reluctant to be held accountable for decisions and ministers demanding to make all the decisions.

Both need to be reversed.

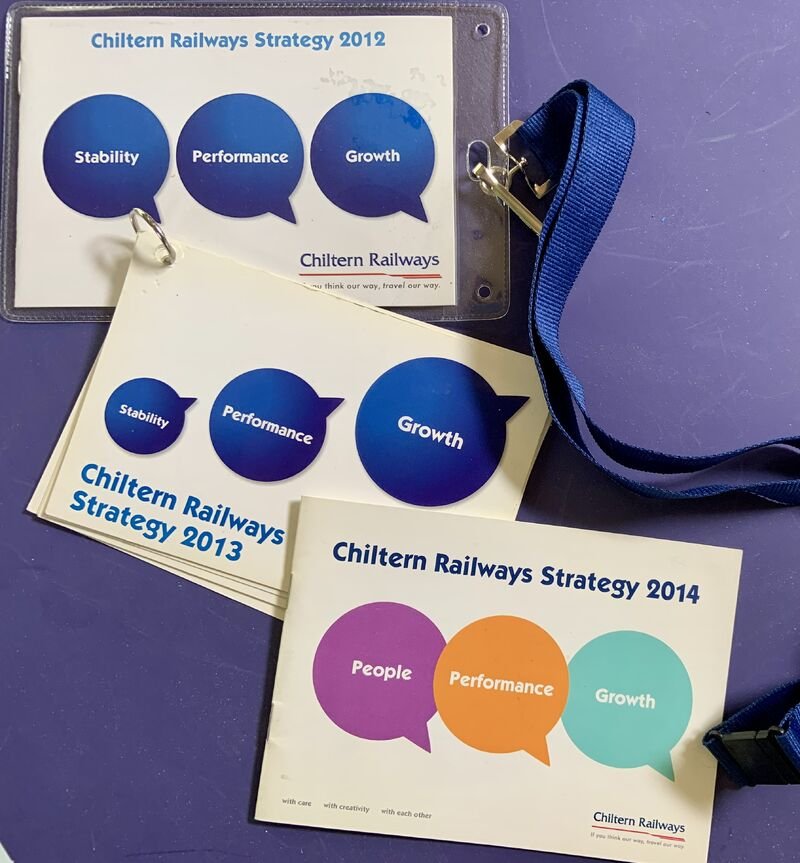

For an illustration of just how much of a difference it can make, read this blog post about the building of our Chiltern Railways extension to Oxford.

While you’re unlikely to be involved in building a new railway, as you read it, you can immediately see how empowerment and accountability meant the job got done faster and cheaper - and better.

That could be your world too!

4) Lose the “Daily Mail Test”

Have you heard about the Daily Mail test?

It’s widespread in the public sector.

It basically means “don’t do anything the Daily Mail might criticise”.

There’s a problem, however.

The Daily Mail criticises literally everything.

The day after the final of Celebrity Traitors, the Daily Mail published this:

When you read the article, however, it turns out that there is literally zero evidence it was a fix, or that Alan’s tears were fake.

All they’ve done is found some people who posted on X that they thought they were.

There is litereally no way of avoiding being criticised by the Daily Mail, so it’s time to abandon the Daily Mail test.

5) Provide Innovation Budgets

Once we’ve lost (some!) of our fear of the Daily Mail, then allocate an amount of money to innovation experiments.

Be explicit on what the fund is for.

It’s there to enable local managers to try things - without requiring the level of certainty we normally expect.

We can justify this expenditure because of all the multitudinous evidence that the cheapest way to discover what good looks like is to try it.

But to do that, we need to be able to back peoples’ ideas and hunches and allow them to develop real-world evidence.

As you can hear in my interivew with Jonny Mood, Director of the National Audit Office, he couldn’t be more explicit: running experiments to try things in the real world is fine, and some of those experiments will fail. As he put it to me, “It's fine when you're swinging big to have a few misses in a controlled environment”. And he’s literally the guy in charge of deciding if money’s been well spent.

Not the Daily Mail.

6) Empower through Strategy

A number of years ago, I wrote this blog post which chuckled at teh fact that one of TfL’s strengths was that it is forced, by law, to write clear strategies.

Wouldn’t it be great, I pondered, if the central Government that had (rightly) made this a requirement for TfL practised what it preached.

Well, now’s the chance.

As I spoke about last week, empowerment only works if there’s absolute clarity as to the destination in mind.

The problem is that “strategy” (as interpreted by Whitehall) tends to be a very long, detailed document that takes months (frequently years) to assemble and is invariably out-of-date by the time it is published.

I’m talking about something very different.

Here’s a reminder of what we meant by “Strategy” at Chiltern Railways:

Dominic Cummings rather wrecked the reputation of three-word slogans (“Hands, face, space”, “Get Brexit Done”, etc) but I’m something of a fan (of the slogans. Not of Cummings).

Ministers need to be super-clear on what they want and super-brief in saying it.

As at Chiltern Railways, make it fit on a lanyard.

7) Challenge Every Process

So often Whitehall is about Doing It The Right Way.

Challenge it when it’s not helpful.

When designing things for the public, it’s essential to consult them.

But does that have to mean a Consultation.

Consultation processes often generate far more heat than light.

Can co-creation forums be a better means of consulting? Can running A-B experiments? Can

8) Learn How to Iterate

Very few us live our lives by planning everything we’re going to do in enormous detail and then executing that written plan.

“On the 17th November 2027, I’m going to win an innovation contract with Great British Railways. That evening, I’m going to complete redecorating the dining room.”

Of course we don’t! Even if I’d very much like to support Great British Railways with their innovation (and, if their future leadership team are reading this, please note), I don’t have the agency to plan at that level of detail.

Even where I do have the agency, like redecorating the dining room, it’s ludicrous to forecast precisely when I’ll do it in two years time: what if my mum gets ill?

No, far better to say that my overall goals are that I do interesting work that matches my skills and knowledge, and that the house is kept to a decorative standard to maintain value and that my wife and I like.

At the moment, I expect that working for GBR and redecorating the dining room might be ways of achieving those goals but other, better ones may occur. In the short term, though, I’m making sure I keep up-to-speed with rail industry reform and saving enough to rededocorate a room each year.

In the same way, in our organisations, it’s crucial we know what we’re trying to achieve, but we don’t have to decide everything up front.

It’s actually far more efficient not to. I previously wrote this blog post which uses the analogy of a journey to Cornwall to try to make this point. I’m still not 100% certain if it works, so please tell me if you think it does.

If you want some confidence that this is something that Government wants to happen, then just look at the “Test, Learn and Grow” programme launched by the Cabinet Office earlier this year. They are absolutely explicit that they want projects to start with end users, build something small and iterate from there.

9) Learn what an agile and innovative organisation looks like

Organisations that are good at this stuff have norms of behaviour. Some of these are quite subtle. I described some of them in this series of blog posts.

This is where I can do a plug for my day job: I’ve spent a long time working on what makes an organisation agile.

Because you need a cheesy acronym, I’ve called it the RACE² model, but other cheesy acronyms are available.

But if you want it to add up to RACE (twice), then the list looks like this:

Resources

Authority

Culture

Expectations

Recognition

Agility

Customer Connectedness

Empowerment

Within each of those, there are norms of behaviour that collectively makes a place move at pace.

I can help you learn what they are - and identify how close you currently are to perfection with each.

10) Don’t Rely on Consultants

The British public sector sometimes struggles to delegate accountability to empowered and competent officials because they don’t exist.

The knowledge and skill that would make for a competent official have been repeatedly outsourced to consultants, with the result that the official who’s commissioning the work struggles to validate it.

As the consultant doesn’t have the authority, the result is that the decision is made by default as opposed to proactively.

Here’s my cut out ‘n’ keep guide for when to use consultants (and when not to)

11) Avoid decision-making by committee

There are certain decisions that need to be made by defined groups: frequently Boards.

They are comparatively rare.

Otherwise, there is no requirement in law that committees need to make decisions.

Committees slow things down (simply down to scheduling) and will generally moderate a decision down to a lowest common denominator of groupthink (whatever everyone’s least uncomfortable with).

So be cautious about delegating to a committee, as opposed to a person.

11) Create a Quanto

Don’t we all love a Quango?

No? Oh.

Quangos have a terribly unfair reputation.

The term stands for QUasi-Autonomous Non-Governmental Organisation.

For some reason, if 500 people work as central Government civil servants, they’re lost in the roundings.

But if their work is hived off into a dedicated body to do the same work, suddenly they’re a waste of money.

However, Quangos have a useful role, in enabling public sector organisations to renew their culture.

Transport for London isn’t a true Quango as it’s not owned by a Government department, but the moment it replaced London Regional Transport in 2000 was a moment of huge cultural renewal for transport in London.

Even though it was the same people doing the same job with the same roundel, TfL was born with a more entrepreneurial, agile, innovative culture. That was set by its first Chair, Ken Livingstone, and reinforced through the people he appointed.

The creation of Great British Railways is another such moment. It’s absolutely critical that GBR is born with the agile and innovative culture it is going to need. Its creation is a once-in-an-organisational lifetime’s chance to create it.

12) Don’t be too collaborative

We’ve ended up in a world in which collaboration is seen rather like green vegetables: the more the better.

In reality, it’s like coffee: a certain amount enhances performance but too much is actively harmful.

The public sector is a collaborative environment. But that means that multiple internal stakeholders have vetoes by default.

At the start of any piece of work, define those people who need to be involved and be explicit that this is it. Try to limit the number of those people to single digits.

It’s a culture change but, hey, all of this is a culture change.

The culture needs to change, so why not here - and with you?

“As Low as Reasonably Practicable.” Have we forgotten the “Reasonably?”

Safety is the number one priority but it can’t be the only priority, or nothing would ever move. Getting the balance right is tough.

“Oh, be reasonable!” is something we’ve all said to our spouse, boyfriend or girlfriend.

But what is being “reasonable”?

That’s a surprisingly difficult question to answer.

The concept of “reasonable” comes up throughout English law. Criminal convictions must be beyond “reasonable” doubt, contracts often require consent not to be “unreasonably” withheld and negligence is when actions fall short of what is “reasonable”.

But nowhere in law is “reasonable” defined.

That inherent flexibility is the concept’s greatest strength: it is subjective and forces you to think. What would the reasonable person think? And, yes, the “reasonable person” exists in law and, no, they are not further defined.

ALARP

In the world of transport and mobility, we encounter reasonableness in the context of “ALARP”.

ALARP is a key principle in risk management, particularly in occupational health and safety. It requires that safety measures and policies must reduce risks to a level that is As Low As “Reasonably Practicable”. This involves a balance between the level of risk and the time, trouble, cost, and physical difficulty of taking measures to avoid or reduce the risk.

The law, however, doesn’t provide guidance as to what actually is “reasonable”.

Seal the windows?

One of the more memorable Exec meetings I was involved in when I was Commercial Director of Chiltern Railways involved an ALARP conversation.

This was when we still operated a handful of older mark 3 carriages with droplight opening windows in the vestibules.

The conversation we were having followed on from an extraordinary episode in which a customer had found himself on a train running non-stop to Bicester when he intended to travel to Beaconsfield.

Instead of doing what you or I would have done (travelled to Bicester and got another train back), he did what seemed to him - in that moment - the obvious thing to do. He went to the vestibule, dropped the window, waited until the train passed through a station (at 80mph) and threw himself out.

The idea, I think, was that he would then wait for a train to Beaconsfield.

He, of course, did not succeed in doing so, as he suffered multiple injuries from the fall though - thankfully and miraculously - he survived.

When the Police interviewed him in hospital, they were expecting to find evidence of mental illness, but he was quite sane. He was someone who found themselves on the wrong train and didn’t deal with it particularly well.

The conversation in this Exec meeting was what we should do.

After all, this customer had demonstrated a risk that we had not successfully mitigated: that someone could quite deliberately open the window and hurl themselves out of a moving train.

The first option was signage. After all, there was nothing in the train that advised passengers on the inadvisability of jumping out of it when it was moving. Signs are cheap and easy to put up - and is often the first response (which is why so many stations are now a festival of warnings and instructions). But would it have actually mitigated the risk? After all, there was already a notice warning not to “lean” out and, surely, he couldn’t have got to leaping without first leaning.

At the other extreme, we could have withdrawn the trains from service. This would have entirely mitigated the risk. However, it would have resulted in a significant reduction in peak time capacity. Other trains would have been overcrowded and, very likely, some people who would now have to stand every day would have decided they’d rather drive their own car. These people would then have had a vastly higher risk of death or injury than they did previously: even if the death or injury would have occurred on someone else’s network, not ours.

In the end, we concluded that the combination of door locks and signage on the trains already had reduced the risk of people falling out to the lowest level that was reasonably practicable. Preventing someone from deliberately hurling themselves out of the train could only be mitigated at disproportionate impact. Other actions, like signage, would have been performative and ineffective.

So we did nothing and it never happened again. Those carriages have now been withdrawn.

Safety first

Now, I don’t want to give you the impression that “reasonable” means easy. It does not mean that there’s no need to take actions just because they are hard to do.

We only had one Exec meeting on droplight windows but we had many on ATP.

ATP stands for Automatic Train Protection, and it was a system that prevented trains passing red signals. Given that red signals prevent collisions, this is a very good thing to do. So back in the 1990s, British Rail created two experimental ATP systems. One of these was installed on part of the Chiltern Railways route.

By 2011, the system was virtually obsolete and the manufacturer warned us of their intention to stop supporting it.

Given that virtually every other railway in the country operated without it (and was fine), surely we should just accept that and move on?

But the problem is that it was practicable to keep it going. It was a bloody nightmare and it was expensive but it was practicable. And given the nature of the risks that ATP mitigated, it was reasonable to do so.

But, of course, it wouldn’t be practicable forever.

What we were seeking to do was to minimise risk. That didn’t have to be achieved through this precise system.

So my colleagues in engineering spent many (many!) hours figuring out alternatives that would achieve the same net risk reduction across the route but with supported technology and eventually settled on an enhanced version of the industry-standard Train Protection Warning System (TPWS).

I am no longer at Chiltern Railways but I suspect that ATP (now into its fourth decade of life) is probably - somehow - still going, while the enhanced TPWS is being installed. Though maybe it’s now enjoying a well-earned retirement.

Either way, in this case, reasonably practicable meant a huge amount of hard work.

As Low as Reasonably Practicable

The problem with a flexible definition is everyone can decide what is reasonable.

If there is expected bad weather, is it practicable to reduce risk?

Yes.

Is it practicable to reduce risk to zero?

Yes.

How?

Don’t run any trains.

A number of years ago, that would have been considered an absurd solution. Yes, it eliminates risk but people who still need to travel will still travel - just on less safe forms of transport.

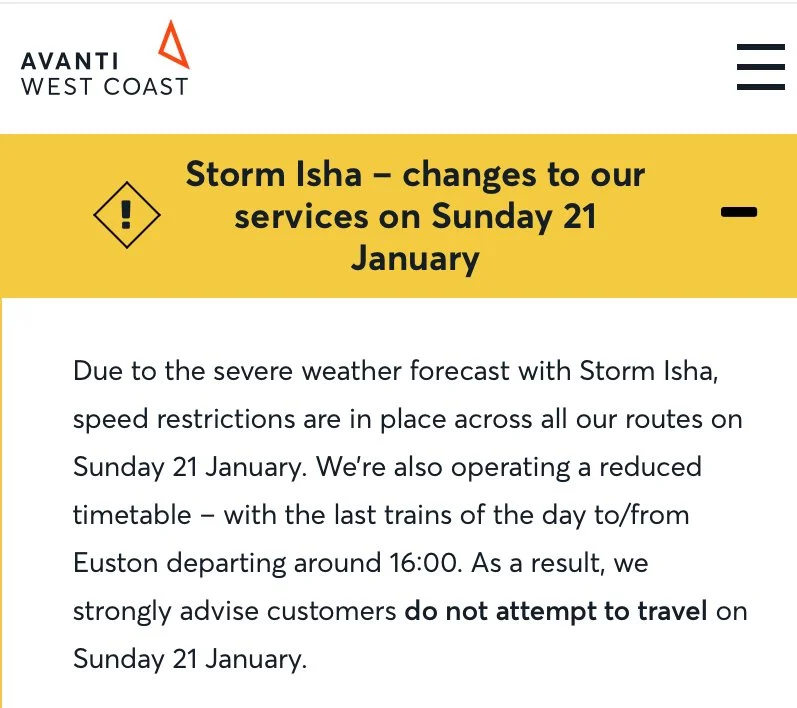

Here’s one of many examples: Storm Isha in January 2024.

And here’s the service update for Avanti West Coast, Britain’s most important transport artery, stretching the word “changes” in the title to breaking point:

And here’s the equivalent from National Express coaches, a form of transport without dedicated infrastructure and much greater risk of collision, for the same day:

National Express could also have prevented risk by pre-emptively cancelling everything.

But while such a course of action would have been practicable, it wouldn’t have been reasonable.

As transport services are here to provide transport.

Avanti running at 125 would create unacceptable risk. But did that mean it needed to shut down entirely? What is reasonable? The folk at Avanti had to make a judgement call but the benchmark for pushing people from the safest mode of land transport to less safe modes should be very high.

Two ends of the telescope

As someone who’s spent a lifetime promoting transport innovation, I’ve certainly seen (many!) occasions when the industry’s safety culture has made innovation slower or harder to achieve.

Good!

Because I’ve also seen this question through the other end of the telescope.

Back in 2008, my then employer National Express was involved in a horrific accident. A coach overturned on a slipway of the M1. I was the nearest person to the site and was first to the hospital where the injured had been taken.

I vividly remember being the only person in the hospital with a National Express name badge. Even more vividly, I remember being in the intensive care ward in which one of our customers was lying covered in tubes and her boyfriend was shouting at me that I’d killed her.

(I do realise, obviously, that he was shouting at my name badge, not at me - but it’s a tough gig trying to apologise to someone when they are holding you responsible for a potentially fatal injury to the love of their life. I’m glad to report that she did, in the event, survive).

This is the kind of thing that can happen when a risk is not ALARP.

But the magic of ALARP is that it does include that ambiguous, ethereal, enigmatic little word “reasonable”.

It would have been utterly unreasonable to strip out ATP from Chiltern Railways just because virtually no other passengers benefited from equivalent levels of protection.

But, equally, it would have been utterly unreasonable to withdraw our slam door trains from service.

And - just as important - putting a sticker on the window would have been performative nonsense.

I’m very glad we didn’t do that.

And I’m also glad that my former Chiltern Railways colleagues kept running during Storm Isha, even when Avanti stopped.

What do you think? Is there a balance between innovation and safety? Should we have put a sticker on the window? Tell me what you think.

Don’t tell anyone but Cycling in London is now rather good

Cycle infrastructure in London is becoming good. Digital information is not.

As we unlock, I’m starting to have more in-person meetings.

One of the curious things about this is that, with lots of people working from home, these tend to be in suburban coffee bars as opposed to central London offices.

The other day, I did a veritable tour of London; starting in my home in Walthamstow, then visiting Spitalfields, Bermondsey, Stoke Newington, Clapton and back to Walthamstow.

That day, I cycled 20 miles across North, South and East London and felt entirely safe. Pretty much the entire journey was either on dedicated cycle lanes, or quiet roads deliberately closed to traffic but permeable to bikes.

It made me realise that we’ve now reached the tipping point in which London is a great city to cycle round; at least in significant parts.

Yet, bizarrely, almost no-one knows.

Had I relied on CityMapper for my journey planning, I’d have ended up going down the A10:

At least Citymapper had me cross the Thames on London Bridge (which has a cycle lane). Google would have me crushed between the traffic and the fence on Tower Bridge:

While specialist app City Cyclist would have had me wheel my bike down Joiner Street as part of my trip. Unfortunately, Joiner Street is the least streety street in London, as it’s actually part of London Bridge station:

By far the worst was TfL’s own journey planner. (I think TfL Go may want me dead). Waltham Forest received £30 million of TfL funding for cycling infrastructure a few years ago, yet TfL’s app sends me on a route that avoids all of it.

Leyton High Road is just one of miles of utterly unsuitable roads that the app navigated me along, despite alternatives being available. No-one would take a second cycle ride if they attempted to follow the route suggested by TfL’s own app for their first:

Despite it being possible to do my full 20-mile journey in ease and safety, every mainstream route planning app would have sent me along roads that were dangerous, unsuitable or both - at least for part of the journey.

This is symptomatic of a curious thing: TfL has done a superb job in achieving the Mayor’s active travel goals, but it’s not so easy to discover.

The problem comes into three categories:

1) Data

2) Legacy

3) Coordination

Data

There is no single dataset that grades roads according to how suitable they are for cycling. As a result, every journey planner uses its own set of rules.

By far the best (and the only one that came up with truly safe routes) is the Cycle.Travel website run by Richard Fairhurst, but it is barely known to the person in the street. Richard and his team have had to put vast amounts of effort into manually adjusting their rules to compensate for the lack of simple datasets.

Given the prevalence of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, this is made all the more important as - frequently - the best routes to cycle along are not main roads with dedicated cycle lanes, but residential streets with a flowerpot in the middle.

It’s frustrating, as TfL have created what they report is the world’s largest cycling database. It surveys every road in London and includes both binary data (e.g. cycle lane yes/no) and 480,000 photographs. Unfortunately, the data and photos largely date from 2017/8 and are now out of date. Excellent cycle routes are avoided by journey planners using this data because the data doesn’t know that they are excellent cycle routes. In many cases, TfL’s own database isn’t aware of improvements made with TfL funding.

Moreover, the tickbox nature of the database just doesn’t work. As an illustration, look at the photo below (this is one of the roads TfL Go routed me down on my way to Spitalfields). According to the TfL database, it benefits from an advisory cycle lane in a differentiated colour, cycle signage and cycle road markings.

And, of course, it does indeed have all those things. But it’s entirely irrelevant as the signage is out of date, the cycle lane is buried beneath parked cars for its entire length and the road markings are ignored:

Legacy

This data problem is hugely compounded by the fact that there is a dataset for a London-wide cycling network. It’s called the London Cycle Network (LCN) and it was a project that ran from 2001 to 2010. During that period, a 900km long London-wide network of signed cycle routes was created. The signs are largely all still in place and many mapping companies incorporated LCN data. Apple Maps is one of them which is why, I suspect, I was sent down the road photographed above, as it’s a London Cycle Network road.

But the LCN is now entirely out of date. The photo above shows a road in Waltham Forest, in which TfL have invested £30m upgrading cycling infrastructure on virtually every other road except this one. This is almost the only road in Waltham Forest you wouldn’t want to cycle down - but it’s the one the TfL app sends you down, because it’s relying on a provider that is using a legacy dataset.

It’s absolutely critical that the LCN is reactivated and updated. The road photographed above should not be considered part of a cycle network but until the LCN is formally updated, it will remain so by default.

Coordination

The third big issue is that the London-wide network of cycle routes has been developed in dribs and drabs through different projects and funding pots; and they don’t gel together.

On my journey from Walthamstow to Spitalfields (i.e. the way I actually go, not the way any of the apps would send me), I start on the C23 cycleway and then move onto the Q2 cycleway. The Q2 was a TfL project delivered by the boroughs, while the C23 was a borough project delivered using TfL funding. As a result, the C23 stops on the border of Waltham Forest, around 30 yards from the Q2. Someone cycling up the Q2 would have no idea that the C23 (an outstanding route with dedicated, segregated cycle lanes its entire length) starts just out of line of sight.

If you go onto the TfL website to look for a map of cycle routes, you will easily find one. It’s the TfL “Cycleways” map and it shows all the TfL Cycleways. But only the TfL Cycleways. In Walthamstow, we are also served by the National Cycle Network Route 1 but this entirely traffic-free route is missing from the TfL map as it is not a TfL Cycleway. As are many other safe routes that happen not to have been created as a TfL cycleway.

One of the most useful cycle routes in central London is the East-West corridor across Bloomsbury and Fitzrovia along Torrington Place (and a bunch of other roads). It comprises entirely segregated cycle lanes in both directions but it pre-dates the Cycleways programme so doesn’t make the map:

All over London, lack of coordination means that cycling feels more like a series of individual schemes than a coordinated network.

Sweat the small stuff

Cycling in London at the moment is a bit like trying to use the bus network if none of the buses had destinations and only some of them had numbers. It’s perfectly do-able but it’s a lot more effort than it should be, and most people - frankly - won’t bother.

Given that in 2016 TfL committed to spend £154m per year on cycling infrastructure and then increased it further during the pandemic, it’s a real shame that so much expenditure and effort is underutilised.

Getting a single version of the truth dataset would not be super easy as definitions of cycle quality would need to be created that reflect actual experience as opposed to just infrastructure. But cycling benefits from a passionate lobby and if the definitions were right, the data could be crowdsourced. Updating the London Cycle Network requires ongoing operational investment.

To be honest, in terms of usage, spending what it takes on getting the data right (and to update the London Cycle Network) would be a much better use of the next tranch of cash than building more infrastructure that is hard to find - and it certainly wouldn’t take £154m.

It’s cycles + buses, not cycles or buses

I’ve written on these pages previously on this point, so I won’t repeat myself. Suffice to say that it’s all about alternatives to the car. That means that more cycling is good and more buses is good. The challenge is making sure that new cycle infrastructure is at the expense of cars (thus creating an incentive for modal shift) and not at the expense of buses.

A bus lane is not a prospective cycle lane; it is a bus lane and we need more of them. Given that bus speeds have been falling in London for much of the last decade, it’s critical that the new cycle infrastructure is an enabler to car-free living (which will benefit all modes of transport). When schemes are developed, the detailed choices made on each occasion must have as the goal to maximise the attractiveness of the high density and low carbon modes of transport. That means buses and bikes - and not cars.